Online Teaching and Learning (Chapters)

Chapter 9: Assessments and Grading

Assessments and Grading

Assessments and Grading

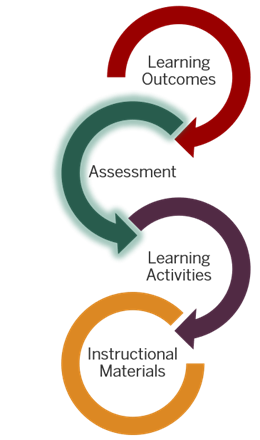

The most effective way to ensure that online students get the feedback they need to stay on track is through an assessment plan that includes both formative and summative assessments.

Formative Assessment

There are two main purposes of formative assessment

- to help students see what they know and don’t know and to fill in the gaps in their understanding, and

- to help instructors see both individual gaps and patterns of misunderstanding across the course to provide timely support.

It’s assessment for learning instead of assessment of learning

In an online course, it’s especially important for students to get frequent feedback on how they’re doing and formative assessment can fill that need. Examples of basic formative assessments include classroom assessment techniques (CATs) such as muddiest point or one-sentence summary activities.

Online courses lend themselves nicely to the use of automatically-graded “knowledge checks.” After completing one, students can quickly receive feedback based on the answers they chose in a multiple-choice section or compare their answers to those of an expert in a short essay section.

Another option for formative assessment is to break a larger, summative assessment into smaller pieces that can be turned in throughout the semester. This allows you to catch and address misconceptions, challenge students’ early analyses, and provide the opportunity for them to revise and resubmit the individual pieces as a unified whole at the end of the semester or unit.

An often overlooked option for formative assessment is peer review and feedback. When adequately scaffolded, peer review and critique can be a learning activity for both the student giving and the student receiving the peer review. The Assignments tool in Canvas provides options for blind peer review, or you can set up a small group discussion where students post their thoughts, explanations, or examples and then provide feedback to the person posting immediately above them.

Summative Assessment

In contrast to formative assessment, summative assessment is designed to provide evidence of how well students have achieved a learning outcome or otherwise gained skills or knowledge throughout the course.

It is the assessment of learning, in contrast with the assessment for learning provided by formative assessment.

Although the assessment methods that often first come to mind are tests, papers, or lab exercises, many other activities can be used for assessment, including portfolios, discussion forums, concept maps, diagrams, and presentations. You can also use assessment methods in a variety of different ways. For example, multiple-choice test items can be developed to draw attention to contextual factors in an authentic case. In the same way, artificial and minimally contextualized cases can be used to identify who, what, when, and where without asking students to work with holistic, complex problems. Click on the headings below to see more about different types of assessments.

While it’s easy to incorporate media into Assessments and Discussions, you need to keep in mind that not all online students will have the ability to easily create and upload media. Planning ahead with an alternate activity for students with technology and internet access limitations will make it much easier when the need arises.

Rubrics

Rubrics

Rubrics are defined as “a guide listing specific criteria for grading or scoring academic papers, projects, or tests.” They act as both assessment tools for faculty and learning tools for students, and they can ease anxiety about the grading process for both parties. Creating rubrics does require a substantial time investment upfront, but this process will result in reduced time spent grading or explaining assignment criteria down the road.

Research indicates that rubrics:

- Encourage students to think critically by linking assignments with learning objectives.

- Increase transparency and consistency in grading by helping to normalize the work of multiple graders, such as across multiple sections of a course or with TAs sharing grading tasks in large courses.

- Reduce student concerns about subjectivity or arbitrariness in grading.

- Increase the efficiency of grading by reducing the time you spend grading assignments and supporting the provision of timely feedback which has a positive impact on the learning process.

- Support formative assessment when coupled with other forms of feedback (e.g., brief, individualized comments) to show students how to improve.

- Enhance the quality of self- and peer-assessment by giving students a clear sense of what constitutes different levels of performance.

For some rubric examples, take a look at the following resources:

- The AAC&U VALUE rubrics

- Examples of different types of rubrics from the Berkeley Graduate Student Teaching Resource Center

- John Mueller’s Authentic Assessment Toolbox descriptions using rubrics with authentic assessment (The page is really yellow which makes it hard to read but there is some good stuff there.)

Grading Tips

This professor discusses the importance of including clear course grading and assessment policies:

Other Grading Options

In some courses, an easy way to speed up grading is to develop a bank of comments. When you have taught a course multiple times, you know the common errors and misconceptions that occur. To save re-typing basically the same comment over and over, save the comment either with your answer key or in a more general comment file for the module or course and then copy and paste it in, personalizing it as needed.

If you find that, despite your best efforts, you are having trouble keeping up with grading and interaction, it is all right to stop and re-assess what you are doing and what you are asking your students to do. A mid-semester check-in with your students via an anonymous survey is a good way to find out if they are also feeling overwhelmed, lacking connection, not understanding what is expected of them, or needing a different kind of feedback.

Academic Honesty

Dealing with cheating and plagiarism when grading can take up time that is better spent on other things. Plagiarism checkers such as Safe Assign or Turnitin can be used by you to identify and document plagiarism and as a teaching tool to help students learn to better cite sources when quoting or paraphrasing.

Assignments can also be designed to reduce the likelihood of cheating. Jo Ann Vogt at The Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning at IUB offers the following suggestions:

- Ground assignments in real-world events or in controversies in your field.

- Require students to incorporate a specific source/quotation/set of statistics/table, etc.

- Limit acceptable sources to a specific time period—say, the past 1 or 2 years.

- Structure assignments in stages with multiple due dates so that you can see students’ ideas/arguments develop.

- Require drafts of longer assignments, and ask students to submit links to all sources.

- Assign genres other than essays and reports. Proposals, letters to the editor, and recommendation memos require independent thinking and analysis.

- Teach students to paraphrase and show them examples of proper paraphrasing and citation.

In high-stakes testing situations, remote proctoring services can allow students to take assessments at any time using their own computer while proctors monitor and record their webcams, physical environments, and desktops. Issues with proctoring include student concerns about privacy, increased anxiety because of the unfamiliar proctoring situation, difficulty in finding a private place to take the assessment uninterrupted, and difficulty in maintaining internet connection.

Course Participation

When teaching on campus, it is not uncommon to have attendance factor into a course grade. It is fairly straightforward—students show up for class, they mostly pay attention, they may speak up in a class discussion or work in a small group. You give them a grade at the end of the semester. Online classes with no required synchronous components can be trickier. Depending on the course level and content, some instructors may substitute an auto-graded quiz over the reading or video or an assignment like a minute paper where they write briefly about one or two things in the module.

In some in-person courses, participation is presumed by attendance. Students who are present are, by default, considered to be participating. As you have likely seen in many class settings, that presumption is not always true. While answering a question or submitting a quiz is enough to prove attendance for financial aid reporting purposes, it doesn’t provide the level of engagement that we hope to see in an online class.

Just as in your physical classroom, different approaches will engage different students, and it may take some experimentation to find out what works best for your course. Having a variety of participatory activities the first couple of times you teach a given course can allow you to gauge which ones you want to keep and which ones you don’t.

Expectations for active participation

There are three main expectations that both faculty and students should be able to have regarding active participation in an online class and they don’t have anything to do with word count, logins, or liking posts.

The first expectation should be that participating will help students learn or practice something that supports a desired learning outcome. The connection needs to be made explicitly enough that students can see the point of the interaction. When students feel that participation is merely busywork with no real benefit to them, they are much less likely to take part and benefit from the interaction. Explaining your participation activities transparently can clarify the purpose and benefit for your students and yourself.

Another expectation is that actively participating in the course should be worth a reasonable amount of the course grade. Supporting online presence through active learning and collaboration won’t happen by itself. Instructors modeling active participation in a welcoming and supportive manner will certainly help, but students are just as likely to look at what is included in the final grade to determine what is important. If you are encouraging weekly substantive participation but all of those activities together only count for 5% of the course grade, students will get the impression that their participation is not really valued. Putting your money (grades) where your mouth is, reinforces to students the value of active learning and collaboration for their academic success.

The final expectation is that all students can authentically participate. Your students are a diverse group, so assuming that everyone has had similar experiences, similar access to technology and internet connection, or similar comfort levels sharing their experiences and thoughts with their classmates is not going to be true for everyone.

Grading Participation

While active participation and engagement are crucial for learning, when that participation becomes fixed in text or video form, grading the quality and level of participation can become a challenge because you can have a lot of actual artifacts to grade. Depending on the activities involved, instructors may grade each activity individually or grade sets of activities related to single topics or projects along with providing general feedback on what the student has done well and what could be improved.

Rubrics can be an effective way of setting everyone’s expectations for participation in class and smaller group discussions and making participation grades more transparent. Quality Matters encourages the use of a checklist or rubric for participation; the rubric or checklist may include items such as originality, quality of posts, and responsiveness to peers.

Here are some example discussion rubrics to help you think about what you might work well in your own class.

- General Grading Rubric for Class Discussion – Google Doc from Online Learning Insights

- Rubric from Modeling and Assessing Online Discussions for Faculty Development presentation at Mid-Atlantic Regional Educause Conference

- Two discussion rubrics from the University of Wisconsin-Stout and one from Northern Arizona University (pdf, 176k)

Group Work

Group work is challenging for many students in a face-to-face class. When you add the extra layers of complication from technology and asynchronous communication, it’s not surprising that some faculty simply avoid assigning group work in an online class. However, group work supports active learning and provides students with opportunities to connect with one another, lessening the isolation often felt in online classes. How you design and scaffold group work can either help or hinder students as they try to complete the tasks involved.

Group work can be made easier for both students and faculty if expectations and norms are set in advance. Providing netiquette rules, a rubric for participation, peer evaluation, and attaching points to positive group interaction will motivate most students to participate at a meaningful level—especially if the group assignment is relevant and authentic.

It helps to start group work after the first few weeks in the semester to allow students time to acclimate to the course and get to know each other through introductions. Both Budhai (2016) and Chang and Kang (2016) recommend keeping groups small and odd-numbered. Budhai also recommends intentionally creating teams, setting clear expectations for individual contributions, and monitoring the online group space if possible to catch issues before they escalate.

A useful option in certain types of group work is to assign functional roles to students with responsibility for certain process-oriented tasks. Roles such as starter, elaborater, source-searcher, theoretician, questioner, devil’s advocate, moderator, and wrapper are common to discussion-based and case study projects. Assigning roles in advance allows students to develop group cohesion and feelings of responsibility sooner and decreases the amount of time it takes groups to coordinate who is doing what, allowing them to get started on actual task-focused work faster.

Grading Group Work

When you set up an assignment as a group assignment, you have the option of giving all students the same grade or grading each student individually. If you want to give everyone the same grade on the assignment but adjust for individual contributions and participation, there are a couple of common ways to do that. The cleanest way is to set the group assignment to give all students the same grades so that you only have to provide feedback in one place where all group members can see it. You can then either change the setting in the assignment to give different grades to different students after grading the group as a whole or include a second assignment for an individualized grade.

However you gather information on individual contributions and participation, it is very helpful to include a rubric for students to use when assessing each other’s performance. Group participation rubrics can be as simple or as complex as you would like them to be. They range from something as basic as:

Rate your team members (including yourself) on a scale of 1 to 10 on

- Quality of participation

- Quantity of participation

- Timeliness of participation

or, to keep students from giving everyone maximum scores to “be nice,”

Imagine you earn $100 for this project. Pay each member of your group (including yourself) according to the quantity and quality of their participation in the project.

For something more complex, see this rubric from Carnegie Mellon and other sample rubrics and peer evaluation forms available from the Carnegie Mellon Eberly Center on Teaching Excellence.

Additional Grading Challenges

Chang and Kang (2016) describe and address the challenges facing group work online, specifically looking at aspects such as group size, responsibility, coordination, structure, and leadership. When collaboration and shared knowledge construction isn’t critical, one way to address the common challenge of lack of commitment and responsibility by some group members is to structure the assignment as cooperative group work instead of collaborative group work. Working cooperatively, students are engaged with and responsible for separate parts of the project and come together to compile, edit, and present their work. This way, active students are not held back waiting for information from a non-participating member. The instructor can define the individual tasks and work products and then let the group choose who does what or assign individual tasks to specific students.

The following three-part series on online group work from Online Learning Insights briefly explains several effective strategies for using group work in online classes.

- Five Elements that Promote Learner Collaboration and Group Work in Online Courses;

- Five Essential Skills Instructors Need to Facilitate Online Group Work & Collaboration; and

- Student Perceptions of Online Group Work: What They Really Think and How to Make it Work

Chapter Questions

- Create a visual representation (table, image, etc..) comparing and contrasting the use of summative and formative assessments in online courses.

- Describe one formative assessment that an online instructor can use to meet learning objectives.

- Evaluate two alternative assessment methods (beyond traditional tests and papers) that can be used to assess students’ skills and knowledge in an online course.

- Find and evaluate a rubric for an online course.

- Illustrate a time when group work may be useful in an online course.

- Identify two strategies instructors can implement to address the challenges associated with group work.