6 Chapter 6: Art of ancient Egypt, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East

Maria Americo

Chapter 6: Art of ancient Egypt, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East

Here in chapter 6, we will explore ancient art from Egypt, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East. Let’s begin.

Canopic Jar with a Lid Depicting a Queen

Egypt

1349–1330 BCE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

We begin with one of the most famous aspects of ancient Egyptian history and archaeology: the world of the ancient Egyptian mummy.

This is a canopic jar, an alabaster vessel in which the internal organs of a deceased person were housed and placed in the coffin along with the person’s mummy—so that, upon using some magical incantations after arriving in the afterlife, the person could gain use of their organs again. This particular example of a canopic jar has an interesting history of its own, both ancient and archaeological. The canopic jar, and the remains inside, are thought to belong to one of the women in the family of the famous Pharaoh Akhenaten, who was possibly the father of the most famous ancient Egyptian pharaoh of them all, King Tut. The jar was found in the Valley of the Kings, a burial site for many of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs, and it was discovered by a British archaeologist, during the height of colonialist archaeology.

Egypt has often been a site for non-native archaeologists excavating ancient objects and “donating” them to museums outside of Egypt—that is how this canopic jar reached the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, for example. There has also been extensive, and invasive, studies of all kinds performed on ancient Egypt’s mummies, including DNA testing. Egyptology is one area of ancient history where we can see the blending of “old-fashioned” historical research with the use of modern technology: for example, researchers are able to “see inside” a canopic jar like this one not by smashing it open to see what’s inside, but by methods like CT scanning, X-ray, and MRI imaging. We can only imagine what ancient folks would have thought of our methods of learning more about who they were.

Questions for reflection

1. Describe the face depicted at the top of this canopic jar. Can you tell anything about this person, or the life they might have lived, based on this depiction?

2. What do you think of the “ethics” of studying mummies or other ancient human remains? Is it disrespectful to the dead to study them in this way?

3. What do you think of the practice of “colonialist archaeology”? Should people from outside of a country be allowed to practice archaeology there? Where should discoveries from these excavations be kept?

4. To whom do ancient objects “belong”?

Sources and further reading for this art

Uncovering the mysteries of an Ancient Egyptian canopic jar – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credo Reference – Ancient (archaeogenetics)

Sphinx of Hatshepsut

Egypt

1479–1458 BCE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This granite statue of a sphinx belonged to Hatshepsut, another of the most famous pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Hatshepsut is one of few examples of a female ruler in antiquity. She began her reign as the regent of a young male relative of hers, but later became senior co-ruler of Egypt along with him. Her reign is known for the reestablishing of trade routes between Egypt and areas in the Middle East, and for her extensive building projects. But today, Hatshepsut is perhaps best known for the way she chose to depict herself as an Egyptian pharaoh.

In most of her statuary and other depictions, Pharaoh Hatshepsut chose to have herself represented according to the standards of a male Egyptian king, with a beard, facial features in keeping with the ideal standard of beauty for ancient Egyptian men, and the clothing and headdress of a male pharaoh. Some of her images, however, depict her as a woman. Pharoah Hatshepsut’s varying choices for her own self-depiction show the options that were available to a person of her time in terms of gender and self-representation.

In this particular portrait, Hatshepsut is neither man nor woman, but a hybrid being: her head (represented here in a more masculine fashion) on the body of a lion, a mythological creature called a sphinx. We see evidence for the mythology and representation of sphinxes (or hybrid creatures incorporating human, lion, and other elements) across ancient cultures, from Greece to Egypt. Perhaps, for example, you have heard of the riddle of the sphinx?

Questions for reflection

- Does anything about this portrayal of Pharaoh Hatshepsut look “masculine” to you? Or “feminine”?

- Describe the “lion” portion of this statue. Does it look like an anatomically correct lion, or is it stylized? Do you think it was made by someone who had seen a lion in real life?

- What other mythological creatures have you heard of? What do you know about their myths or stories?

Sources and further reading for this art

3.

Buddha Offering Protection

India

late 6th–early 7th century CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

As the religion and practice of Buddhism developed over the centuries of antiquity, sculpture and statuary became a very important part of Buddhist art. Every sculpture and statue of Buddhist art is rich with symbol and iconography.

For example, this is a statue of the Buddha, and all of its attributes indicate the inner state of the Buddha, qualities like inner peace, wisdom, welcome, and compassion. There were certain physical features that Buddhist artists used to “signal” that they were depicting a figure of the Buddha, like the webbing between his fingers and long earlobes, both of which we can see in this statue. The Buddha depicted here wears a simple robe, indicating his devotion to the lifestyle of a monk. Finally, with one hand the Buddha performs a mudra, a hand gesture with symbolic meaning. This mudra is called Abhaya in Sanskrit, and it is a gesture meant to evoke feelings of safety, reassurance, the easing of fear, and divine protection. If you have ever attended a yoga class, it is likely that you, too, have encountered a mudra. Perhaps the most famous mudra is called Anjali mudra in Sanskrit; in a yoga class you will likely hear it called “prayer position.”

Questions for reflection

- Describe the overall vibe and emotional mood of this statue of the Buddha. How did the artist use small artistic details to create this vibe and emotional mood?

- Do you see traces of color on this statue? Where? Many pieces of ancient art from around the world used to be brilliantly colored. Why do their colors no longer survive?

- Imagine the life of a Buddhist monk in ancient times. What do you think ancient monks’ lives were like?

Sources and further reading for this art

Enlightened Technology: Radiographing an Image of the Buddha | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Art of Gandhara in The Metropolitan Museum of Art – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

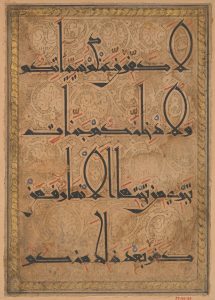

Folio from a Qur’an Manuscript

Iran or Afghanistan

1180 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

The Qur’an manuscript from which this folio originally came is what art historians and archaeologists sometimes call a “luxury object.” This object also gives us the opportunity to learn a few new art historical terms and ideas. A manuscript (in archaeology and art history) is a document that was written by hand. In premodern times, before the invention of any kind of mechanical printing, all text was written by hand—no other method of text production existed. A folio refers to a single page of a manuscript. This folio shows parts of sura 5 of the Qur’an, verses 12-13 and 22-24. It was created during an Islamic dynasty that we call the Seljuqs, who ruled from their homeland in today’s Iran during Late Antiquity.

“Luxury object” is a little bit less straightforward to define. Luxury objects are sometimes so designated because they were expensive, rare, or used materials that were not easy to obtain. Sometimes they are so designated because owning them was a marker of wealth, socioeconomic status, profession, education, or some other form of identity. By all of those metrics, we could call this Qur’an folio a “luxury object.” The calligrapher who created this used not only colored ink but even gold leaf to write the Qur’anic verses. The style of calligraphy in which this Qur’an manuscript was written clearly points to a high level of skill, technique, and education—it requires training in order to be able to create calligraphy of this style. And it would have required some amount of wealth and status for someone to have been able to pay for and own this Qur’an.

We should also remember that owning a book at all in premodern times was a marker of wealth, education, and status. Not everyone could read. Not everyone owned books. And certainly not everyone had the means to own a fancy and expensive book like this one. In premodern times, to a certain extent, all books were “luxury objects.”

Questions for Reflection

- Describe this object in close detail. What shapes and colors do you see here?

- What materials were used to create this object?

- Are holy or religious objects “pieces of art”?

- Imagine the schooling or training the calligrapher of this piece received, in order to be able to create a text like this.

Sources and further reading for this art

Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credo Reference – Calligraphy (Islamic)

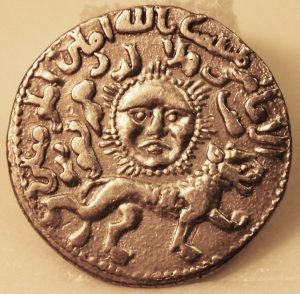

Astrological coin

Turkey

dated to 1240-41 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This silver coin, minted in ancient Turkey, depicts astrological imagery: an anthropomorphized sun with a face, and a lion. The lion could represent the zodiac sign Leo, or it might be a personification of the ideal ruler, who was thought to have the qualities of the lion, like power, majesty, leadership, and strength. Zodiacal imagery was quite popular in ancient Islamic art, sometimes simply as decoration, sometimes as a way to indicate time of year (as each zodiac sign is associated with a different season, month, or time during the year), and even for its astrological meanings. Astrology was also quite popular in ancient Islamic culture, as it was in nearly every single culture worldwide in ancient times.

The study of ancient coins is called numismatics; a researcher who studies ancient coinage is called a numismatist. This particular kind of coin is exciting to numismatists, and helps all of us learn more about history, because the civilization that minted it has stamped on it when it was made, and by whom. The inscription on this coin tells us (in Arabic, the language of the Islamic empires at that time) that it was minted by a ruler named Din Kai Khusrau II (who ruled from 1239–46 CE) in the year 638 AH. (AH, or “anno hegirae” in Latin, is an Islamic dating system based on events in the life of the Prophet Muhammad, much like the BC/AD dating system is based on events in the life of Jesus Christ.) 638 AH is equivalent to sometime in the years 1240-41 CE.

Numismatics is one of the most important subcategories of ancient studies. Coins are some of the most numerous objects found in all archaeological excavations. And coins can tell us so much about a culture: what symbols were important to them, what materials they had access to, where they traded and traveled, how standardized their government was, and who their rulers were and when they lived. Coins give us a microcosm view into the macrocosm of an ancient culture.

Questions for reflection

- Describe all of the images on this coin in careful detail.

- What do you think the lion on this coin symbolizes? What about the sun?

- How do coins teach us about history? How can we learn about cultures’ important symbols, access to materials, and trade patterns through coin discoveries?

- Think of a modern-day coin or other piece of currency that you have seen. What image is on it? What does that image symbolize? Why is it meaningful to the culture that created that coin?

- If you minted a coin with a symbol that was meaningful to you, or that represented who you are, what symbol would you choose?

Sources and further reading for this art

Following the Stars: Images of the Zodiac in Islamic Art – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Media Attributions

- canopic jar

- blue sphinx

- Buddha Offering Protection

- Folio from a Qur’an Manuscript

- silver lion coin