3 Chapter 3: Art of prehistory (and peoples with undeciphered languages)

Maria Americo

Chapter 3: Art of prehistory (and peoples with undeciphered languages)

Welcome to our first “art” chapter!

In chapter 3, we begin our exploration of historical study through art in the prehistoric period. We will allow the 5 art pieces we will explore in this chapter to help us understand what the word prehistoric means in historical and archaeological research, as well as some other details, ideas, and lived experiences relevant to the prehistoric period.

Each of our 5 pieces of art will include its date and place of creation, an attribution and link to its source, and a few questions for you, the reader and observer, to connect with and consider the art more deeply.

Let’s get started.

Marble female figure

2600–2400 BCE

Cycladic Islands

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This figure comes from a pre-ancient-Greek civilization that we call “Cycladic.” We call the civilization who created this piece of art the Cycladic civilization because they lived in the Cycladic Islands, a group of small islands in the Aegean Sea that is now part of the country of Greece. We have “named” this civilization after their geographic region because we do not know what the people may have called themselves. There are no written records left behind from the Cycladic people. We call an ancient civilization that left behind no writings prehistoric.

Many figurines of this type have been found in the Cycladic Islands by archaeologists, and nearly all of them were discovered in tombs, as burial treasure for the deceased. These figurines became very popular in research and even as inspiration for art upon their discovery beginning in the 1800s. They are sometimes called “modern,” “angular,” and even “abstract.”

These figurines are also sometimes a source of mystery, since we are not sure what they were used for (if anything). But modern-day research often considers whether these figurines were “goddesses” or representations of fertility, because of the presence of breasts sculpted onto the figurines, and the way they hold their arms wrapped around their torsos. You’ll be invited now to consider these details of the Cycladic figurine for yourself.

Questions for reflection

1. Describe this piece of art. What do you see here?

2. Why did our ancient ancestors bury objects like this one in the tombs of their deceased?

3. Why have some researchers called objects of this type “representations of goddesses” or “fertility figures”? Do you agree with this identification of the figurine? What details about it lead you towards, or away from, that identification?

4. How can we learn about ancient civilizations that left behind no written records?

5. Is this figurine a “work of art”? Do you think that idea existed in ancient times?

Sources & further reading on this artwork

Who Were the Early Cycladic Figures? – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Stamp seal: buffalo with incense burner(?)

Indus River Valley

2600–1900 BCE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This object comes from a civilization that we call the Indus River Valley Civilization. Much like the Cycladic people whom we discussed earlier, we call these people the Indus River Valley Civilization because of where they lived (the basins of the Indus River in Southeast Asia) and because we do not know what they may have called themselves. There is evidence for writing that survives from the Indus River Valley Civilization, but it is as yet undeciphered.

This object is known as a “stamp seal.” It is made out of steatite that has been fired and glazed, a process that hardens and preserves a material so that it can survive—sometimes for many thousands of years, like this object! Steatite is a kind of soapstone, mainly made of the mineral talc. It is a relatively soft stone, easy to carve, which makes it an ideal material for an object like a stamp seal.

Stamp seals provide historical evidence for us of standardization and even a kind of mass production in antiquity. The way a stamp seal worked is that the user would place the stamp facedown in a malleable material, like clay, in order to create an impression—a mark, so that anyone who saw the impression would know whom, or where, the communication came from. The same stamp could, of course, be used again and again, creating a sort of standard “logo” or “signature” for a person, place, or institution. Because the writing on this seal is still undeciphered, we do not know what it says. But researchers hypothesize that seals like this one were used to indicate ownership of trade products (which also, of course, gives us some evidence for trade, commerce, travel, and communication across different ancient societies). If a merchant placed this stamp seal on their goods, anyone who came across them would know that they had come from someone in the Indus River Valley.

Questions for reflection

- What animals and objects are featured in the image on this stamp seal? What do you think they symbolize?

- Where is the writing on this object? Make some guess about what it says.

- Would someone in ancient times have needed to be literate in order to “read” this seal—to know which merchant or place it came from?

- If you were to create a visual “logo” for yourself, what would it include?

Source & further reading on this artwork

The Art of South and Southeast Asia: A Resource for Educators – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bird Head

Morobe province, Papua New Guinea

Date unknown

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this artwork and find the image source here.

This object was not found by professional archaeologists, unlike the two that we have already explored in this chapter. Instead, it was simply unearthed by local people in Papua New Guinea, which is an island nation in the Pacific Ocean, north of Australia. Outside of the professional and academic discipline that we call archaeology, people all over the world have always discovered their own local premodern history while gardening or digging for other reasons, or even when animals dig or root in the ground. This sculpted head of a bird was found via that method: by chance, by local people on their own land.

Researchers are not sure exactly when this ancient object was made, what it was used for, or what we should call the civilization that made it; we can only say that it was made by an unidentified prehistoric culture in the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea. The sculpture may be a representation of a bird called the cassowary, an ostrich-like bird that is native to Papua New Guinea, and which is still considered a divine, holy, and powerful bird by contemporary local people in Papua New Guinea today.

As you observe this artwork, you may notice that it holds traces of red paint. However, art historians believe that the red paint was not added to the object by its original creators, but by later users, who unearthed the object, believed that it had been created by spirits, and used it in magical and ritual contexts. Many ancient objects go on to be reused and find new life in this way, especially in religious and ritual situations.

Questions for reflection

- Describe this object. What do you see here?

- Take some time to describe the shapes that you see on this sculpture. How does the use of shape help us understand and identify this object as the head of a bird?

- What kind of ritual do you think this object was used in?

- Have you ever heard other stories of “regular people” (i.e., not archaeologists or other researchers) digging up ancient objects or fossils?

Source & further reading for this artwork

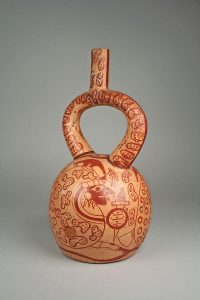

Stirrup-spout bottle with bean warriors

Moche artist(s), Peru

500–800 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this artwork and find the image source here.

This object comes from the Moche culture, a people on the north coast of Peru in ancient times. There are no written records that survive from the Moche culture, but archaeologists have found a large collection of art and objects from ancient Peru that help paint a picture of what this civilization may have been like.

In the fantastical imagery on this bottle, four warriors in the shape of lima beans fight one another. The lima bean warriors have faces, military headdresses, weaponry and shields, and even a single leg each, extended in a way that suggests dynamic movement. Lima beans are native to Peru, and have been cultivated there for thousands of years. The beans may have represented large numbers and multiplicity or power and danger, since raw beans can be toxic—making them a good choice of symbol for the strength of a warrior or the large size of an army.

Ancient cultures around the world created and used ceramic vessels like this one, and every time period and region has its own distinctive style. The shape of this bottle, for example, is thought to perhaps have prevented evaporation of the liquids that would have been kept inside, or perhaps simply to make the vessel easier to carry. It is important for us as modern-day observers of ancient vessels like this one to remember that, while we can (usually) only study the vessels themselves, in ancient times at least some of the value in these objects would have been held in what the objects contained—perhaps water, liquor, oil, or other liquids. Unless some traces of what these vessels originally held is still present inside them, we can only study the containers in modern times, not what they contained. When studying ancient ceramic vessels, don’t forget: it’s what’s inside that counts!

Questions for reflection

- Describe what you see here. Can you see the lima bean warriors represented on this object?

- Why do you think lima beans were chosen as a symbolism for warriors, combat, or strength?

- Presenting lima beans as warriors is an artistic technique known as anthropomorphizing, which means “giving animals, plants, or other beings human-like qualities.” Do you know of any other anthropomorphic art? Do we still use this technique in art today? Are you surprised that this artistic style and idea existed in ancient times?

- What do you think this object was used for in ancient times? What liquid do you think it contained?

- This is a functional object, meaning that it served a purpose (as a container for liquids) in ancient times. Is it still “art”? Why or why not?

Source & further reading for this artwork

Ancient Peruvian Ceramics: The Nathan Cummings Collection – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

5.

Levallois Core

Middle Paleolithic Period, Egypt

240,000–40,000 BCE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this artwork and find the image source here.

A Levallois Core is a stone that has been shaped into a tool for use by humans according to a special technique that was developed during the Middle Paleolithic Period (the middle part of the “Old Stone Age”). It’s important to understand where these “names” for historical periods come from. Like all the artworks here in chapter 3, this piece was made by a culture that left behind no writing (or at least no writing that we can presently understand). This piece is prehistoric, which means, again, that it comes from a time period from which we have no evidence of written language. We do not know what the people who made this piece called themselves, if they called themselves anything at all. We also do not know what they called the age of time that they lived in, if they called it anything. No one woke up one day around the year 240,000 BCE and declared, “Today is the beginning of the Middle Paleolithic (Old Stone) Age.” Instead, we as historians look back and name these periods of history ourselves, as we note patterns, innovations, and new inventions over time. Many ancient historical time periods are named after new materials that people learned to work with during those times—so the New, Middle, and Old Stone Ages are so named because it was during that time that our ancient human ancestors learned how to work with stone.

This Levallois Core is the oldest object we will explore together in this book. In fact, it is so old that it coincides with the evolutionary development of earlier species of Hominin into modern Homo sapiens, the kind of humans that we are today. Techniques like hunting, the harnessing of fire to create weapons and tools, and the use of shape and symbols, are what help distinguish us humans from our earlier Hominid ancestors, and what helped us develop the behavior and anatomy of Homo sapiens. And if we define art as the expression of an idea, symbol, skill, or technique in an external object, then art is one of the things that literally makes us who we are.

Questions for reflection

- Do you believe that this object is art? Why or why not? How does your answer help you define your own idea boundaries about what art is, and what it is not?

- Imagine the everyday life of the early human ancestor who created and/or used this object.

- What details of this object let us know that it was carved into this shape on purpose, and not by accident or via natural methods like weather, erosion, or “wear and tear” over time?

- Do you believe that art (or the creation of objects using skill and technique) is something that separates humans from other species or animals?

Sources & further reading on this artwork

Levallois Core | Middle Paleolithic Period | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Media Attributions

- marble female figure

- stamp seal

- bird head

- lima bean warriors

- levallois core