10 Chapter 10: The art of ancient science

Maria Americo

Chapter 10: The art of ancient science

Because this textbook is being developed in part for our Saint Peter’s University course entitled the History of Ancient Science, in chapter 10 we will explore some of the artistic and archaeological discoveries of ancient science. Let’s do it.

Horizontal sundial

British

1720 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

Of any premodern scientific object, we have the most surviving examples of the sundial. Our ancient ancestors have been telling time using sundials since classical antiquity, and human understanding of the same 24-hour day and 365-day year that we still observe goes back several millennia. We are still living in the same universe as our most ancient ancestors, with the same seasonal and cosmic markers of time.

How do sundials work? They tell time via the movement of the sun through the sky during the day. A raised element casts a shadow in the sun on the surface of the sundial, where (in the best, most accurate examples of premodern sundials) there is a precise grid for marking the hours, which we call the grid or system of hour lines; wherever the sun’s shadow falls on that grid tells the user the time of day. Obviously we have new methods for telling time these days, but you might still encounter a sundial, perhaps in a garden or other public outdoor space. Have you ever seen a sundial before?

Questions for reflection

- Describe this sundial in careful detail. What color is it? What material is it made of? Do you see the different sundial elements, like the shadow caster and the grid of hour lines?

- Do you think this sundial was a luxury object? Who could have owned and used this sundial?

- What other methods of telling time do you think people had in ancient times?

Source and further reading for this art

Water clock decorated with a baboon

Egypt

650 BCE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this artwork and find the image source here.

We have explored one scientific object that helped people tell time in the premodern world: the sundial. But the times and places where a sundial can be used to tell time are limited: the user has to be outside, and the sun has to be shining. How did people tell time when they were in other situations, for example, when they were inside?

One object that helped people tell time while they were inside, or when the sun wasn’t shining, is called a water clock. This is an example of a water clock from ancient Egypt. The design of a water clock is simple: water flows out of a vessel that has a spout of some kind. In some examples of water clocks, the vessel that the water flows out of has graduation marks inside: as more of these graduation marks are revealed as water flows out, the intervals of time passing are indicated.

What kind of time does a water clock, or other “outflow” timekeeping device, make us aware of? Water clocks, and modern-day examples of “outflow” timekeeping objects like the hourglass, do not tell us what hour or time it is. Instead, they tell us that a fixed interval or amount of time has gone by. What amount of time? The amount of time measured by an outflow timekeeping device is set by the device’s creator. For example, in a traditional hourglass, once all the sand has flowed down to the bottom chamber of the glass, one hour has gone by. The skill and understanding of the passage and keeping of time is encoded into the object by the person who measured and made it. This particular water clock was likely dedicated to the Egyptian deity Thoth, as an offering at his temple. Thoth was the ancient Egyptian god of reckoning, mathematics, timekeeping, writing, and other kinds of intellectual knowledge and understanding.

Ancient water clocks were used in situations where different things needed to happen for an equal amount of time. One place where they were often used was in legal courts: if different witnesses, lawyers, or other people needed to be allowed to speak for equal lengths of time, in order to keep the legal process fair, water clocks were used to ensure that everyone had the same amount of time to speak and present their case.

Questions for reflection

- Describe all elements of this water clock in detail. What is it made of? Do you see the “inflow” and “outflow” openings of this water clock?

- What do you think the clock’s baboon imagery symbolizes?

- Imagine the context in which this ancient water clock might have been used. When did our ancient ancestors need to keep track of the passage of time in this way?

- Have you ever used, or seen, a modern-day “outflow” timekeeping device, like an hourglass or even a digital countdown or timer on your phone? What do people use these kinds of timekeeping devices for in modern times?

Sources and further reading for this art

Egyptian Art – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

3.

Astrolabe

Yemen

690 AH / 1290 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

An astrolabe was an astronomical object in use during the Late Antique, medieval, and early modern periods. It helped travelers and astronomers with a variety of “problems” of astronomy; for example, it aided in navigation via the stars, in timekeeping, in tracking lunar and solar eclipses, in determining latitude, and even in land surveying (because there is a link between the sciences of astronomy and geography!).

Astrolabes are also works of art. They represent great skill, knowledge, and understanding of mathematics, timekeeping, and the astronomical workings of our universe. They also are elaborately and delicately made, displaying the impressive craftsmanship of the metalworkers who created them. And they also showcase artistic skill, with many decorative details and beautiful diagrams of the stars. This astrolabe comes from ancient Yemen—we know the name of its creator and its exact date of creation, since it was dated and signed!—and is an example of the great discoveries and innovations that were being made in the Late Antique Middle East during that era of scientific history.

Questions for reflection

- Notice and describe all of the small details of the construction of this astrolabe. What do you see here?

- What is this object made out of? What color is it?

- Is this object a work of art? Is it a luxury object?

- Imagine something of the life of the person who owned this object. Where, when, and for what purpose did they use it?

Sources and further reading for this art

Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

4.

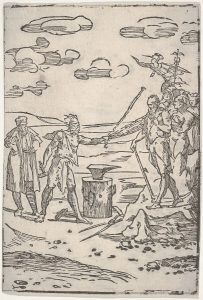

Woodcut from the series “The various operations of alchemy”

Italy

1540-50 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

One of the most intriguing, and historically fascinating, fields of ancient science was the one that we call alchemy. In its simplest definition, alchemy was a practical craft and experimental process by which alchemists tried to transform cheaper metals, like copper and lead, into silver and gold, much more valuable metals. How did alchemists try to “transform” one thing into another? Oftentimes they practiced in an ancient form of a laboratory, attempting various “ancient chemistry” experiments like heating and cooling metals, pouring different substances onto metals, trying to dissolve metals, and many other physically transformative processes. You may notice, in looking at the two words alchemy and chemistry, that they share a word element, “chem.” This is because alchemy eventually developed, via a historical process, into the modern-day science of chemistry.

Alchemy, however, also had a more mystical, esoteric, and even mysterious side. One reason for this was practical: because alchemists were trying to transform cheaper metals into more expensive ones, and because metals like copper and gold were used to make coinage—money!—in historical times, premodern governments often assumed that alchemists aimed to create counterfeit money, and therefore tried to outlaw the practice of alchemy. So alchemists often had to practice their craft in secret, encoding their texts and diagrams with strange symbols that only insiders could understand. And the practice itself also had a more mystical version—after all, if it is possible to change one metal into another, what other kinds of magical changes might we humans be capable of? Could we improve our bodies? Could we improve our souls? Could we find some way to live forever?

Questions for reflection

- Describe this image in careful detail. What do you see here? What objects do you see? What people do you see, and how are they interacting?

- The central object in this image is called an anvil (it’s sitting on top of the tree stump). An anvil is one of the tools of a blacksmith or metalworker. Why would alchemists have made good blacksmiths or metalworkers, creating objects like weapons and armor?

- Alchemical texts and diagrams use the language of symbols. Do you see any symbols in this image? Notice, if you can, the winged staff with snakes wrapped around it. Have you ever seen that symbol before? What does it mean?

- Have you ever used a code or secret language to keep sensitive information safe?

Sources and further reading for this art

Woodcut | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

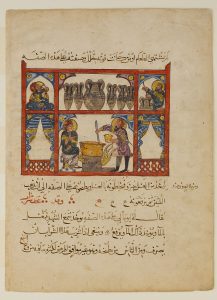

“Preparing Medicine from Honey,” a folio from a manuscript of an Arabic translation of an ancient Greek medical text

Iraq

dated 621 AH / 1224 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Find the image source and learn more about this art here.

In the Late Antique Islamic world, government leaders, eager to encourage scientific and medical discoveries in the lands they ruled, sponsored the arts and sciences. This was a new historical development; the governments of classical antiquity did not pay people to do math or science, and these were not activities that made money, so only people from wealthy families could spend their time studying science or math. In the Late Antique Middle East, that situation changed.

One of the projects the Islamic governments sponsored was the translation of ancient texts about math, science, and medicine from ancient languages like Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, and Persian into their current language, Arabic. Once they had access to all those foundational texts in math, science, and medicine, current Arabic-speaking researchers could use them as inspiration for making their own discoveries and inventions. We call this historical process the Islamic translation movement.

This is an illuminated manuscript folio from an Arabic translation of an ancient Greek medical text. In the illumination on this folio, an ancient pharmacist prepares a medication from honey, as a remedy for weakness and loss of appetite. The Metropolitan Museum of Art digital source for this art gives us a translation of the folio’s text:

“… [who] has no appetite or is feeling weak, its prescription is as follows: take one part honey (in the margin is added: and take one part tears [lit. water of eyes]); mix with honey and cook in a pot until two thirds of it is gone; then take it from the pot.

And to make wine called Abū Ma’ālī with this recipe: take beeswax and wash it with water; and that water took out and if this wine drink it must … and some of people cooked it but it is not good for disease because it is a lot of dirty of wax.”

Questions for reflection

- Describe this manuscript folio in careful detail. What do you see here? What colors are here? What objects, figures, and images are here?

- How does the image interact with the text in this manuscript folio?

- Identify the pharmacist in this image. What are they doing?

- This is an ancient medical prescription! How is it different from a modern-day prescription?

- Is this a luxury object? Who would have used this manuscript when it was created?

Sources and further reading for this art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 11, The Islamic World – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Islamic art in the Metropolitan Museum: The Historical Context – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credo Reference – Islamic medicine

Media Attributions

- sundial

- Egyptian water clock

- Yemeni astrolabe

- 2012.136.139

- Arabic medical manuscript