7 Chapter 7: Art of ancient East Asia

Maria Americo

Chapter 7: Art of ancient East Asia

Here in chapter 7, we will explore some artworks from ancient East Asia. Let’s get to it.

Female Dancer

China

2nd century BCE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This ceramic sculpture of a woman comes from a period of Chinese history known as the Han Dynasty, which was a time of great cultural, artistic, literary, political, and military expansion in ancient China. For just one example, in order to become a government official in Han Dynasty China, a political hopeful had to pass something called the “imperial exams.” These exams asked people to prove, along with their knowledge of history and politics, that they could recite, interpret, and even compose their own poetry. This was a time and place of the blending of culture and the arts into every aspect of life.

This beautiful sculpture showcases not only the skill of its creator, but also the beauty and gracefulness of the dancer who is its subject. Of course as an object it is static, it does not move—and yet, even thousands of years later, retains a palpable sense of movement.

Questions for reflection

- Describe this sculpture in careful detail—its coloring, its shape, its bends and curves, the garment the figure wears and how it moves with her, the expression on the dancer’s face, her body language.

- Does the sculpture give you any sense of how this dancer may have felt, or what emotion she is expressing through her dance?

- For whom do you think this sculpture was made? Does it have a “function” or purpose?

- How did the sculptor of this piece create a sense of motion in a static object?

Source and further reading for this art

Samurai armor

Japan

early 14th century CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This elaborate body armor belonged to a samurai. Medieval Japan was characterized by the feudal system, an economic way of life in which wealthy landowners allowed vassals of the lower classes to own and farm portions of their land in exchange for military service and other forms of loyalty. Samurai, soldiers for hire similar in some ways to knights in medieval Europe, were employed by the wealthy landowners to patrol and protect their land.

The samurai have a lasting mythology whose emotional resonance can still be felt today, perhaps because they lived by the samurai code, a philosophy that guided their actions and way of life. This code was known as bushido in Japanese, and required loyalty to one’s master, preferring death in battle above capture or surrender, lack of attachment to material wealth, and even a provision of ritual suicide if necessary. The samurai as a military, economic, and social class ceased to exist around the late 1800s, but the idea of them continues to live on in pop culture memory.

Questions for reflection

- Describe this medieval samurai armor in careful detail. What do you see here? What colors, shapes, materials?

- Imagine how this armor was meant to be worn. How would it feel to wear armor like this? Was it comfortable? Was it heavy?

- Imagine something of the life of the samurai who once wore this armor.

- Why do you think the feudal system ceased to exist? Whom does an economic system like this most serve?

Sources and further reading for this art

Arms and Armor – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

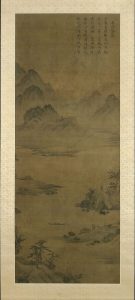

Wild geese descending to sandbar (hanging scroll)

Korea

late 15th–early 16th century CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art, and find the image source (and translation of the poem!), here.

The hanging scroll, made of silk and inscribed with ink, is one of the most important, famous, and recognizable styles of art from premodern Asia. Hanging scrolls combine landscape painting with poetry; a premodern art piece that combines writing and art, with the art sometimes, but not always, depicting the written words, is called illuminated.

Here is a translation of the poem on this illuminated hanging scroll (you can find this translation at the link to this artwork above):

Jade mansions covered in gauze,

A golden river with no rice fields in sight;

Comrades and brothers fly in pairs

Ten thousand miles down [the Rivers] Xiao and Xiang [these rivers are in a region of China that often appears in poetry and literature]

Distant waters like silk streamers,

Flat sandbanks sparkle in frosty sunlight;

By the ferry, near a setting sun, a few men scatter,

Alighting, how carefree the geese look

Questions for reflection

- Describe the landscape scene drawn here. What adjectives would you use to describe the scene, and the way that it was drawn?

- How does the poetry interact with the image? Where was it inscribed? How does it fit in with the image?

- Now that you have read a translation of the poem on this piece of art, do you think the artist’s drawing is depicting, representing, or illuminating the poem? How do the drawing and the poem “work” or “go” together?

- Sketch, doodle, draw, or (if you’re feeling super creative!) even paint an illustration for this poem of your own. Or, write your own poem based on the ink drawing on this scroll.

- Where do you think this scroll was displayed when it was first made? If you had it, where would you display it?

Sources and further reading for this art

The Arts of Korea: A Resource for Educators – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Diamond Mountains: Travel and Nostalgia in Korean Art – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ceremonial instrument in the shape of an axe

Indonesia

100 BCE–300 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

Now that we have reached approximately the midpoint of this textbook, it is time for you to be introduced to the one big art history “joke” that you need to know.

As you have already learned through your journey in this book, the work of the art historian is often characterized by (educated) guesses, imagination, and even historical intuition. History is not about certainty; it is about uncertainty, and being comfortable with uncertainty, because history involves human beings. Human behavior, emotions, decisions, and relationships are not mathematical equations with a single “right answer”; they are dynamic, changeable, unpredictable, and sometimes mysterious.

What this means for our study of art is that we do not always know exactly what a piece of premodern art “meant” or was used for. Art exists in context. And context can get lost over time. So we as art historians do the best we can with the tools we have. We make guesses.

And sometimes, when we simply are not sure what an ancient object was used for, we call it a “ritual object.” This bronze object from ancient Indonesia is an excellent example of this. We are not sure how this object was used, or what it meant for its culture in context. So it is a “ritual object”: ancient, mysterious, culturally significant, perhaps used in some cool, meaningful, and spiritual ritual.

Our best guess for the function of this object is that it was an instrument, meant to be hung from a rope and struck to create a percussive sound during ritual. Many rituals and religious ceremonies, both ancient and modern, involve music, drumming, or sound. Perhaps you, too, have attended a religious ceremony or ritual that involved music or singing, connecting us in this way back to our ancient ancestors.

Questions for reflection

- Describe the shape, markings, color, and overall body of this object.

- What do you think this object was used for? What details of the object lead you in that direction?

- Imagine something of the ritual or religious ceremony in which this object might have been used.

Sources and further reading for this art

Containing the Divine: North Sumatra, Indonesia – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

5.

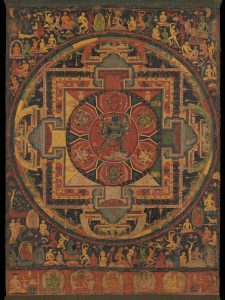

Chakrasamvara Mandala

Nepal

1100 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This large painting on cloth is highly elaborate, detailed, and intense—and there is a reason behind these characteristics of the artwork. This is a mandala, Sanskrit for “circle”; a mandala is a geometric diagram, usually housed in a circle, that is used (in Buddhist, tantric, yogic, and other traditions) for meditation, focusing the mind, or inspiration towards understanding and enlightenment. The colors, details, shapes, tiny landscapes and figures, and geometric patterns provide a focal and gazing point for a spiritual seeker during meditation, allowing them to grasp some aspect of the universe that is depicted within the mandala.

A mandala is “read” from the center moving outwards. This mandala from ancient Nepal depicts, at the center, a deity of Tantric Buddhism known as Chakrasamvara along with his wife, Vajravarahi. They are surrounded by six yogic goddesses. Framing the circle, or mandala, are depictions of burial grounds. The layer at the very bottom of the image, the lowest register (layers of a diagram such as this one are called “registers”), shows other Buddhist religious figures. Let’s read this mandala a little bit more together.

Questions for reflection

- What most jumps out at you in this ancient Nepalese mandala? Where is your eye immediately drawn?

- What colors do you see in this mandala? What is its overall color scheme? Which color stands out to you the most? What does that color mean, evoke, or symbolize?

- What is the “mood” of this mandala?

- The purpose of a mandala during meditation is to provide a gazing point, focusing the mind upon some aspect of universal truth that the mandala depicts. What does it mean that this mandala depicts burial grounds? What aspect of universal truth is it teaching?

- Anyone can meditate. You are invited to practice meditation with this mandala for yourself. Set a timer, perhaps for just one minute, or perhaps 3-5. Simply gaze at this mandala. Take deep breaths. Once your timer goes off, write down anything you saw, felt, or understood during your mandala meditation.

Source and further reading for this art

Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credo Reference – Vajrayana Buddhism (Tantric Buddhism)

Media Attributions

- Female Dancer

- samurai armor

- Korean hanging scroll

- Indonesian ceremonial instrument

- Nepalese mandala