5 Chapter 5: Late antique art

Maria Americo

Chapter 5: Late Antique Art

Welcome to our chapter on Late Antique art. Late Antiquity is a chronological term that historians use for the era from about the year 300 CE through to the start of the medieval period, in about 1000 CE. Let’s get started and take a look at some art from the Late Antique period, from different regions around the world.

Plate with the Battle of David and Goliath

Byzantine

629–30 CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This silver plate comes from a civilization that historians call the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire was what remained of the Roman Empire in Late Antiquity, after the empire began to shrink, grow weaker, and become separated over time, by conquest, war, and changes of capital and center of power.

Byzantine art is dominated by images, scenes, and ideas from Christianity, which was, by that point, the state religion of the empire. This plate was made in Constantinople (today’s Istanbul, the capital of modern-day Turkey). Its main, central image shows the biblical figure David fighting the giant Goliath as their armies engage in combat around them. In the smaller image at the bottom of the plate, we can see David cutting off Goliath’s head. All of the warriors in this image wear the military gear that Byzantine soldiers would have worn, a way that the contemporary creators and viewers of this art were able to see themselves in the ancient religious story.

Questions for reflection

- Describe the scene on this art in detail. What do you see?

- Do you know of any other art that depicts biblical or religious figures or events?

- Why do you think the Byzantines made the religious figures in this art “look like them?”

- What do you think this plate was used for? Was it to eat off of? Was it for everyday use? What other function might this object have served?Source and further reading for this art

Why this plate has one of the most cinematic depictions of David and Goliath – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Textile fragment

Sasanian

6th century CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This textile fragment comes from Late Antique Iran, from the Persian empire in power during that time, which we call the Sasanian Empire. This object is made of a blend of cotton and wool, with red and blue decorations, and is thought to have once been part of a Persian carpet, one of the most famous and culturally significant types of art from the Near and Middle East.

Textiles in general do not survive well from ancient times; their natural fibers can easily deteriorate. We often have to imagine what ancient fabrics, textiles, and clothing looked like from written descriptions of them, or from their depictions in art like paintings and sculptures. One of the reasons why it is so unfortunate that ancient textiles do not survive well, or in great numbers, is because the creation of textiles was often the purview of women in the ancient world. While the creation of Persian carpets at high socioeconomic levels, for example in imperial courts, would have been the job of men, a profession that became standardized and required special training, the origins of textile creation lay with women. Women all over the ancient world, from all social classes, created the clothing and other textiles for their families.

Questions for reflection

Describe this textile fragment in detail. (Fragment is an archaeological term for anything that survives only in part, not complete.)

- What is the condition of this textile fragment?

- Imagine, or draw!, what this Persian carpet might have looked in ancient times, when it was complete.

- What sources do we need to look at if we want to learn more about the lives of women in ancient times?

Sources and further reading for this art

“Textiles in The Metropolitan Museum of Art” – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

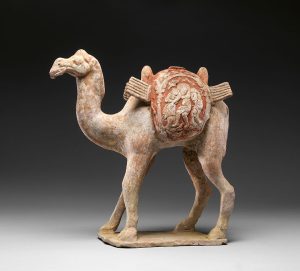

Camel with Dionysian imagery on its saddle bags

China

late 6th–7th century CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

This ceramic figurine of a Bactrian (two-humped) camel from China is another piece that showcases the power and ability of art and ideas to move across borders. The subject of the art, the Bactrian camel, is native to Central Asia. The object was found in a tomb in China, but produced in Central Asia. The camel’s saddle bag features a scene of revelry that may be either Indian or biblical in its origin.

The Bactrian camel figurine is one of countless pieces of art and other material goods that moved across borders via the Silk Road, a complex trading network of both land and sea routes that spanned some four thousand miles, from Southern Europe to East Asia, and along which merchants could buy and sell anything from silk to porcelain and other materials to spices to fabrics and even to fruits, animals, and other natural products. Ideas, religions (especially, throughout Asia, Buddhism), philosophies, and art also traveled along the Silk Road, as objects like this camel can teach us.

Questions for reflection

Describe the figures and the scene on the camel’s saddle bag. What mood does the scene evoke?

- Why was this camel included in someone’s burial treasure? What significance might this animal have held for that person, or within their culture?

- Is this camel depicted in a realistic or a stylized way? Why?

- Imagine the life of a merchant along the Silk Road. What was their experience like?

Source and further reading for this art

4.

Child’s dress

Egypt

660–880 CE (radiocarbon date, 95% probability)

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

We can learn a lot about history through our study of this object, a child’s dress from Late Antique Egypt, in terms of both ancient history as well as the history of modern-day archaeology and art study. As we explored earlier, textiles do not survive well in the archaeological record; their natural fibers tend to deteriorate easily. And this is unfortunate, because textiles, especially clothing such as this piece, are very personal to the wearer. Clothing can express style, age, gender, profession, socioeconomic class, religion, and many other personal details of a human being. Clothing is literally, and metaphorically, held close to a person, and to the body. The low survival rate of archaeological textiles is also unfortunate because, and as we noted earlier, textiles were often created for their families by women, and represented one of women’s most important artistic and economic contributions in the premodern world. We might imagine a mother perhaps having woven this dress for her child.

A detail about this dress can also help us learn more about our modern-day study of ancient objects. This child’s dress has been carbon-dated, an interdisciplinary process of archaeological study that combines science and history. Carbon-dating is a method of determining the age of an ancient object by measuring the presence of radiocarbon (a radioactive isotope of the element carbon that decreases over time) in the object. When we use carbon-dating to determine the age of an ancient object, we can trust that we are getting a fairly accurate understanding of when that object was made.

However, carbon-dating of archaeological objects is actually rather rare. Carbon-dating can be expensive and involves laboratory equipment. It is a technical, specialized process that few archaeologists and art historians themselves are trained in, so it usually requires collaboration among multiple people or institutions. Most ancient archaeological objects are not carbon-dated for these reasons. Usually, the age of an archaeological object is estimated based on where (how deep) or at what level of an excavation the object was found—the idea that there are layers in the ground, and that each layer represents a different era of history, is called stratigraphy. Art historians also usually estimate the dates of premodern objects based on artistic or stylistic patterns and trends that change over time—much the same way we might see an outfit and guess, based on its style, whether it is from the 1960s, 1970s, or 1990s.

Questions for reflection

1. Describe this object in careful detail—its shape, its size, its color, its decoration.

2. Imagine something about the daily life of the child who wore this garment in Late Antique Egypt, or about the person who wove this dress.

3. What kinds of ancient objects do you think are often carbon-dated? Remember that the process of carbon-dating is technical and expensive—what kinds of ancient objects might be considered “worth it?” What kinds of ancient objects would people want to know the exact ages of?

Source and further reading on this art

Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Credo Reference – CARBON-14 DATING

5.

Gold earrings

Korea

6th century CE

-Image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, used under a Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, Public Domain

-Learn more about this art and find the image source here.

Late Antique Korea had a thriving tradition of gold craftsmanship. Wearing intricately designed gold jewelry was a marker of wealth and high social status, and there is evidence that people of all genders wore elaborate gold jewelry in ancient Korea. Earrings such as these are often discovered as burial treasure, interred with people after they pass away. This indicates the importance that this gold jewelry held culturally for people—they valued it so much they did not wish to be away from it, not even after death or in the afterlife.

Human beings have been adorning themselves with jewelry and other ornaments since the very early stages of human history. Jewelry is often recognizable across vast distances of time and space—if you see a beaded necklace for example, or a gold earring, it is likely you will be able to quickly and easily identify it as a piece of jewelry, even if it is many thousands of years old. And jewelry styles endure—many very ancient pieces of jewelry were created in a style similar to what we see in jewelry today. And if you visit any museum gift shop, you will see jewelry for sale that has been inspired by pieces of ancient jewelry. In this way, we remember that art (at least in some ways) is timeless.

Questions for reflection

- Describe all the details of this pair of earrings closely.

- Imagine the life, profession, and social status of the person who wore these earrings.

- Imagine what it would have been like to create these earrings—without the use of modern-day tools and technologies.

- Why do people wear and give each other jewelry, whether in ancient or modern times? Come up with at least 5 different reasons.

Source and further reading on this art

Arts of Korea – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Media Attributions

- Plate with the Battle of David and Goliath

- Textile fragment

- Camel with Dionysian imagery on its saddle bags

- Child’s Dress

- gold earrings