5 Writing Chapter One: Problem and Procedures

Problem and Procedures

Martin LaGrow

Time to Hit the Road

Imagine you’re going on a cross-country road trip covering several stops over a couple of weeks. If you’re like most people, you don’t just jump in the car and start driving, assuming you’ll figure things out when you arrive. Instead, you go to travel websites and learn about the local sights, and use a map app and plan your route. You mark where you’re starting, where you’re going, what major stops or checkpoints you’ll hit, and what you need to be aware of along the way.

That’s exactly what Chapter One of a dissertation does.

Chapter One acts as a map for your readers and for yourself. It lays out:

- Where you’re starting → What’s the background or context of the problem? Why is this issue worth studying?

- Where you’re headed → What are your research questions, objectives, or hypotheses? What’s the purpose of this study?

- Why this route → What’s your rationale? Why did you choose this topic and approach, and why does it matter?

- What’s ahead on the road → What key terms or definitions should the reader know? What will the upcoming chapters cover?

Just like a map keeps you on track and helps prevent you from getting lost, Chapter One helps keep your dissertation focused and lays out the course. Without it, you (and your readers) could easily lose sight of where you’re going. But with a strategically informative map, you’re clear about where you’re going, why you’re going there, and how you’ll get there. It makes the long journey ahead much smoother for you and your readers. Keep in mind, even though you may have done your literature review already, and you are becoming an expert on the subject you’ve chosen to write about, this chapter serves as the first exposure your readers may have to your topic and work. Thus, you should write as though you’re talking to someone who is hearing about it for the first time. Be mindful of this; take the time to set the narrative, and connect your sections to each other as well as to the literature review.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to…

- Identify the differences between the key parts of a qualitative Chapter One and quantitative Chapter One.

- Analyze descriptions and examples of the key parts of Chapter One, and

- use those models and examples to help you construct Chapter One of your research study.

Overview of Key Words and Concepts

This chapter is full of new terms and concepts; in fact, the purpose of this chapter is to introduce you to the parts of Chapter One, so this whole chapter is, in a sense, an overview of the key words and concepts necessary to write Chapter One of your dissertation. However, there is one important key concept to introduce, and that is the difference in focus between a quantitative study and a qualitative one.

Hypotheses and Research Questions

In quantitative research, once you establish your research problem and its significance, you frame your study by stating your driving research questions and then formulating one or more hypothesis and matching null hypothesis (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). In qualitative research, you frame what you will study with research questions (Creswell & Poth, 2018) and you address them directly with your study design. This will be explained in greater detail in this chapter. These elements set the stage for the rest of your dissertation, so it is imperative that they be well framed. Poorly constructed hypotheses and research questions seldom lead to a sound and cohesive research study (Mertens, 2020). In the process of writing your dissertation, even in later chapters, you may find it is necessary to tweak the wording slightly, but the focus of your study must remain untouched unless you are prepared to backtrack and rethink through the literature review process.

Conceptual and Theoretical Frameworks

A conceptual framework refers to the set of concepts, assumptions, beliefs, and theories that support and structure a qualitative research study (Miles, et al., 2014). It is often constructed by the researcher from prior literature, personal experiences, and contextual understanding of the research problem. The conceptual framework maps out how you think the key variables and concepts in a qualitative study relate to each other, and it informs the design, data collection methods, and interpretation of findings. A conceptual framework is rooted in a theoretical perspective, the broad lens through which the author of a dissertation views their study.

In contrast, a theoretical framework is typically drawn from existing, formalized theories or models that offer a lens for understanding the research problem of a quantitative reserach study. While the conceptual framework lays out the “what” in qualitative research (i.e., what constructs you are exploring and how you believe they interact), the theoretical framework explains the “why” by grounding quantitative research in established scholarly theory (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

It should be noted that these interpretations are commonly adopted or adapted from Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (2014) and Creswell and Creswell (2018). This table can help you better understand the key differences between theoretical frameworks, theoretical perspectives, and conceptual frameworks.

In qualitative research, think of your theoretical perspective as your research glasses. It represents how you see the world. Your conceptual framework is the map you draw to guide your route. It shows what matters in your study and how those pieces fit together.

In quantitative research, a theoretical framework is a specific prescription lens in your glasses. It sharpens your focus.

| Term | Definition | Function in Research | Found in… | Example |

| Theoretical Framework | A specific, established theory or model used to interpret or explain phenomena in your study. | Provides a lens to analyze your data. | Quantitative | Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1978) |

| Theoretical Perspective | A broad worldview or philosophical stance about how knowledge is constructed and understood. | Informs how you see the world and approach research. | Qualitative | Constructivism (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) |

| Conceptual Framework | A researcher-constructed set of concepts, assumptions, and relationships guiding the study. | Helps design the study and shows how key concepts relate. | Qualitative | A self-designed diagram showing how motivation, self-efficacy, and support predict persistence in STEM majors. |

While the independent and dependent variables were introduced in the previous chapter, in the quantitative research section below, you will also learn about control variables and extraneous variables, other factors that may need to be taken into account when conducting quantitative research.

Finally, this chapter also introduces limitations and delimitations, two different concepts that are often addressed in one section of Chapter One. Limitations help your reader understand potential outside factors that constrain your study, and delimitations explain limits to the research intentionally placed by the researcher.

The Makeup of Chapter One

Regardless of where you go to school for your doctoral degree, the first chapter of a dissertation research study is structured with some very common components. Although they are not identical from one institution to the next, there will be certain commonalities in language and in how they are organized. Certain elements must be included to provide solid footing for your research study. This chapter will introduce you to the parts of Chapter One in a research study. Due to the differing nature of quantitative research and qualitative research, the parts of Chapter One vary slightly, but significantly. This table shows the recommended outline for Chapter One of a dissertation at Saint Peter’s University. It is possible to vary from this outline, but that should be done in consultation with your mentor and for good reason. Following the table is an explanation of each part of Chapter One depending on which study you’re conducting. Note that some parts are the same, and the text may be repetitive; this is done to improve flow and allow you to focus on one research method or the other. Mixed Methods is not covered separately in this chapter; it naturally will contain elements of both. Creating the design for a mixed methods research study should include input from your mentor.

| Quantitative | Qualitative |

| Introduction | Introduction |

| Statement of the Problem | Statement of the Problem |

| Significance of the Problem | Significance of the Problem |

| Purpose of the Study | Purpose of the Study |

| Research Questions, Hypothesis and Null Hypothesis | Research Questions |

| Identification of Variables and Operational Definitions | Definitions of Key Terms |

| Theoretical Framework | Theoretical Perspective and/or Conceptual Framework |

| Assumptions | Assumptions |

| Limitations and Delimitations | Limitations and Delimitations |

| Summary | Summary |

Before reading on, a word of explanation about this chapter. From this point forward, there are two sections: Chapter One in a Quantitative Study navigates through the content in the left column of the table above. Though some sections have the same or similar names, this portion of the chapter is written to guide you through exactly what is needed to address in a quantitative study.

The section that follows is called, naturally, Chapter One in a Qualitative Study and it follows the right side of the table. It will adequately prepare you to write the sections necessary for a qualitative study.

If you are undecided, or are leaning toward mixed methods research, you may wish to read both sections. However, if you are set on the research design you’re using, you can immediately hone in on the appropriate path below.

Chapter One in a Quantitative Study

Introduction

The introduction to your study provides an overview of the research topic and introduces the general area of study. Many colleges and universities include a section of Chapter One called “Background Information” as well as the introduction. As we are not writing that as a separate section, any background information necessary for the reader to understand the topic should be provided in your introduction.

The introduction provides context. This may be historical, cultural, field specific, or anything else that will help the reader understand the setting for your study. It grabs the reader’s attention by outlining the background, setting the stage for the problem, and explaining why you’ve chosen to write about this topic. Note that the introduction is one section that you will want to revisit when your study has been completed. You may have made changes or adjustments in your approach; you may have learned additional context that will be helpful for your reader to understand before delving into your study. When your paper is nearly complete, re-read your introduction to make sure it still rings true, also identifying new information that could be added as a preview to your study.

Statement of the Problem

The introduction has set the stage and provided the reader with enough context to understand the topic you’ve chosen to write about. The next step is to articulate the specific research problem or issue the study addresses. It explains what gap, inconsistency, or unresolved question exists in the current knowledge or practice and why it needs to be investigated quantitatively. A problem statement can not exist in a vacuum; it absolutely must be grounded in the literature review, and address at least one specifically identified gap in the research.

The following story demonstrates how one fictional student arrived at a problem statement. Your approach should resemble “Jasmine’s” experience.

From Curiosity to Problem Statement – A Quantitative Study Journey

Jasmine is a second-year doctoral student in the Caulfield School of Education. She works full-time as the director of student life at a midsized university. Recently, she noticed something troubling: students who were highly involved in campus activities sometimes had surprisingly low GPAs, while others with almost no extracurricular involvement had excellent academic performance. She began to wonder. Was there any actual relationship between student involvement and GPA, or were these just random observations?

Step 1: Observation and Curiosity

During an end-of-semester leadership retreat, Jasmine shared her observation with a colleague who said, “That would make a great research topic.” This sparked her curiosity to investigate further, but she knew she’d need to frame it in a way that could be tested with numbers.

Step 2: Reviewing the Literature

Jasmine searched peer-reviewed journals and found mixed results. Some studies suggested that moderate involvement in extracurricular activities was positively correlated with GPA, while others found no significant relationship. She noticed that many studies relied on self-reported GPA and involvement hours, and some were conducted at very different types of institutions. Few studies focused specifically on commuter campuses like hers, where students often have work and family obligations.

Step 3: Narrowing the Focus

Because she wanted her study to be measurable and objective, Jasmine decided to examine institutional records rather than self-reports. She realized her university’s student life office tracked both hours of participation in registered campus organizations and official GPA records.

Step 4: Identifying Variables

Jasmine set out to conduct a correlational study and determined her predictor variable would be “hours of participation in registered campus organizations” and her criterion variable would be “cumulative GPA.” She decided to control for variables such as student age and credit load, which might also influence GPA.

Step 5: Writing the Problem Statement

Jasmine’s problem statement emerged:

“Although prior research has explored the relationship between student involvement and academic performance, findings have been inconsistent, and few studies have examined commuter campus populations. At Midstate University, it is unknown whether there is a statistically significant relationship between the number of hours students participate in registered campus organizations and their cumulative GPA. Determining this relationship may help guide programming decisions in student affairs and inform academic advising for commuter students.”

Step 6: Ready for the Next Step

With her problem statement in place, Jasmine could now formulate her research questions, develop hypotheses, and design a quantitative correlational study using existing institutional data.

Significance of the Problem

Once the previous section addresses the question, “What is the problem,” this section answers the question “Why is the problem important?” This section details the potential impact or contribution of the study, showing how the findings could advance knowledge, inform practice, shape policy, or benefit specific groups or fields. Let’s revisit Jasmine. How did she relate the significance of the problem she identified? Notice that not only did Jasmine explain the importance of addressing this problem at her institution, she also set out to explain the value of her study beyond “Midstate University.”

Consider your own problem. It matters to you…it likely matters to the institution and students in your problem. Who else can benefit from the study of your problem?

Is the problem important/relevant?

Jasmine set out to create a sense of relevance for her study…why does it matter? Why should anyone read it?

Understanding the relationship between student involvement and academic performance has important implications for student affairs programming, academic advising, and institutional resource allocation. While previous research has explored connections between extracurricular participation and GPA, findings have been inconsistent and often based on self-reported data from traditional, residential student populations. Little is known about whether these relationships exist in commuter campus contexts, where students often balance academic responsibilities with employment, family obligations, and limited campus presence.

At Midstate University, student life administrators invest significant time and funding to encourage student participation in registered campus organizations. If a statistically significant relationship exists between hours of participation and GPA, this evidence could support increased investment in student engagement programs as a means of promoting academic achievement. Conversely, if no such relationship is found, Midstate University may need to re-evaluate how best to encourage and support commuter students to increase engagement.

This study also contributes to the scholarly literature by focusing on a commuter campus setting, thereby addressing a gap identified in previous research. By using institutional records rather than self-reported measures, the study strengthens the reliability of the data and offers a more objective analysis of the relationship between involvement and academic performance. Findings may inform not only Midstate University’s policies and programming but also serve as a reference for other commuter institutions seeking to optimize both student engagement and academic success.

Purpose of the Study, Research Questions, Hypothesis and Null Hypothesis

These parts may be written as one section, or teased out into separate sections as the writer sees fit–but all should be present in a quantitative study.

These parts may be written as one section, or teased out into separate sections as the writer sees fit–but all should be present in a quantitative study.

Purpose of the Study

This section states the overall purpose (what the study seeks to accomplish). Think of your purpose statement as an “elevator speech.” If someone asked you on an elevator what your research study is about, the purpose statement is a short sentence or two that you could say in common language to answer that question. It should be explicitly stated and clear; the wording of this should state “The purpose of this study is to…” with a few sentences of explanation or context.

Research Questions

In a quantitative study, research questions (typically one to three) serve as the foundation for developing hypotheses (and their corresponding null hypotheses). Their role is to identify the specific relationships or differences that will be statistically tested. Once the hypotheses are stated, the focus of the study shifts from exploration to verification—testing whether the data support or reject the null hypothesis.

The research question establishes what you want to know. The hypothesis specifies the expected direction of the relationship and the null hypothesis provides the statistical counterpart to be tested.

Hypothesis and Null Hypothesis

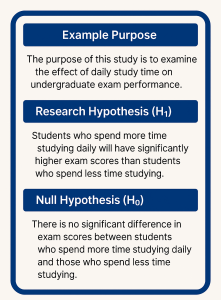

Once the purpose and research questions are identified, you then formally present the research hypothesis (or hypotheses). It is framed as a clear, testable statement predicting the expected relationship or difference between variables. The null hypothesis is also provided, stating that there is no relationship or difference (used for statistical testing). Examples are provided in the infographic (OpenAI, 2025). After this point, the research questions become less visible in the analysis—they have done their job of guiding hypothesis creation. The hypothesis takes center stage for testing and interpretation.

Relation of Research Question to Hypothesis

Dr. Chen designed a quantitative study to examine the relationship between exercise frequency and college students’ perceived stress. Her research question was simple:

Does exercising at least three times per week reduce perceived stress among college students?

From this question, she developed her hypothesis:

Students who exercise three or more times per week will report significantly lower stress levels than students who exercise less frequently.

She also established the null hypothesis to test statistically:

There is no significant difference in perceived stress levels between students who exercise three or more times per week and those who do not.

Once the data were collected and analyzed, Dr. Chen’s focus shifted away from the original research question. The question had already fulfilled its function: it identified the problem and directed the creation of measurable variables and testable hypotheses. At this point, the hypotheses became the focus of the study’s results and interpretation. Statistical tests were used to determine whether the null hypothesis could be rejected and whether the hypothesis was supported.

In other words, the function of the research question was to set the direction and purpose of the study, while the function of the hypothesis was to drive the quantitative testing and interpretation process.

Identification of Variables

The concept of variables is introduced in the previous section under Common Quantitative Research Designs. If you have not yet read that chapter, please begin there as a clear understanding of dependent variables and independent variables is necessary before proceeding.

Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Research Variables

When conducting an experimental or quasi-experimental research study, you must identify your independent and dependent variables involved in the study. Additionally, you may also introduce any other control or extraneous variables as well.

As a reminder, an experimental design tests cause-and-effect relationships by investigating an independent variable (the cause, or predictor) and its impact on a dependent variable (the effect, or outcome). The experimental approach is best used when attempting to answer a question framed as “How does X affect Y?” where X represents the independent variable and Y represents the dependent variable.

In addition to these variables, it may also be necessary to identify any control variables or extraneous variables.

A control variable is a factor that a researcher intentionally keeps the same throughout a study so it does not affect the relationship between the independent variable (the cause) and the dependent variable (the effect). Controlling variables helps ensure that any changes in the dependent variable are really due to the independent variable, not some other factor.

For example, imagine you are studying whether the number of hours students sleep affects their test scores. In this case, sleep hours are the independent variable, and test scores are the dependent variable. But other factors like age, prior GPA, or amount of caffeine consumed could also influence test performance. To make your findings more trustworthy, you would need to find a way to control these variables, and document it in your study. This could mean selecting participants of similar age, collecting data only from students with similar GPAs, or asking all participants to avoid caffeine before the test.

When researchers control variables, they are really asking: “What else might explain this result? How can I prevent that from happening?” By thinking this way, you strengthen your study’s internal validity and increase the confidence that your results are due to the variable you intended to study.

An extraneous variable is any other variable that is not intentionally studied but could still affect the dependent variable if not controlled. They are potential sources of error or “noise” that can distort the findings if they’re not identified and managed. As an example, in the same study about the effect of sleep on test scores, if students’ stress levels or caffeine intake affect their test performance but aren’t accounted for, these would be considered extraneous variables.

Correlational Research Variables

If you are conducting a correlational study, you are not looking for a causal relationship, nor are you manipulating one of the variables, so the independent variable and dependent variable are not utilized the way they are in an experimental approach. Instead, you are simply looking for two variables in existing data, and attempting to identify a relationship between the two (Privitera, 2022). They may be referred to as the primary variable of interest (predictor) and the outcome variable (criterion), as described by Creswell and Creswell (2018). The identification of control variables and extraneous variables still applies.

For example, you suspect that there is a correlation (not a causation) between the amount of time students spend on social media (predictor) and their grade point average (criterion). Investigating the existing data, you look for a pattern to confirm or reject your hypothesis; there is no experiment to conduct.

Descriptive Research Variables

Descriptive studies are not looking for cause and effect or even correlation; they are simply designed to identify characteristics or attributes, usually in an emerging body of knowledge. This kind of variable is a descriptive variable or measured variable; they are simply the data you are gathering and reporting. Descriptive research is seldom if ever done for a research dissertation, for a variety of reasons:

- Descriptive designs look for existing patterns in data, but they stop short of examining why those patterns exist.

- Descriptive studies do not usually test or build upon a theory. Doctoral research is expected to engage with a theoretical or conceptual framework, which guides the interpretation of relationships among variables or the meanings of participants’ experiences.

- Because descriptive studies focus on surface-level data (frequencies, percentages, averages), they do not produce the level of analytical depth or interpretation expected of doctoral work.

An example of a descriptive research variable would be describing teachers’ attitudes toward required homework assignments and measuring them numerically with a Likert scale. The teachers’ overall score(s) represent the descriptive variable. However, descriptive research stops short of analyzing the results. Descriptive research can, however, serve as a foundation for later studies. For example, a master’s thesis or institutional survey might describe patterns that later inspire a doctoral study exploring why those patterns occur.

Operational Definitions

This section provides clear, measurable definitions of key variables or terms used in the study, explaining exactly how each will be observed or measured (e.g., “academic achievement” defined as final GPA).

Note that the operational definitions section is different from the Key Terms and Definitions section of a qualitative study; the purpose is not to provide the meaning of terms, but to establish how the variables are identified and measured in the study.

Theoretical Framework

Here, the researcher identifies the specific theory or model that guides the study and helps explain the expected relationships between variables (e.g., social cognitive theory, self-determination theory). A theoretical perspective is the broad philosophical lens or worldview through which an author of a dissertation views their topic of study. It reflects foundational beliefs about what constitutes knowledge and how it can be known (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Patton, 2015). It provides a foundation for interpreting results.

There are many commonly used theoretical frameworks in education research. For example, if your topic involves behavior change, you might consider Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986). If your focus is on student motivation and engagement, Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) may be more appropriate. Consulting with a research librarian and your mentor are excellent ways to identify a theoretical framework that best fits your study. If you have more than one theoretical framework, you must provide background, an explanation, and a justification for each.

This section of Chapter One should identify the theoretical framework you’ve chosen as the lens to view your study. It should also give background and explanation of the framework, and explain why it was chosen. It is possible to have more than one theoretical framework attached to your study.

The theoretical framework will be revisited in chapter 4 of your study with an explanation as to how your findings connected to your selected theory. Here’s an example illustrating how the theoretical framework connects to the rest of your dissertation. Read about Maya’s experience with forming a theoretical framework before continuing.

What’s the “Why?”

Maya was a doctoral student, deep into designing her quantitative dissertation study on how school administrator leadership styles affect teacher retention rates. She had already crafted her hypothesis and null hypothesis, selected her variables, and planned to run a large-scale survey across several school districts. But during a meeting with her dissertation chair, she learned she was missing the “why.”

“I’m not sure you’ve anchored your work in theory yet,” her mentor said. “What’s the theoretical framework guiding your study?”

Maya had focused so hard on her statistical methods and hypotheses that she hadn’t thought much about why certain leadership behaviors should influence teacher retention. She just knew prior studies showed there was a connection.

Over the next week, Maya dove into the literature and discovered transformational leadership theory (Bass, 1985). This framework explained how leaders who inspire, motivate, and engage their teams tend to foster stronger commitment and job satisfaction. These were exactly the mechanisms she wanted to investigate quantitatively.

By applying transformational leadership theory, Maya was able to sharpen her study. It helped her justify why she chose specific leadership behaviors as independent variables, why she measured teacher satisfaction and retention intention as mediating and dependent variables, and how she expected these relationships to play out statistically.

In the end, the theoretical framework wasn’t an element in Maya’s study that she mentioned once in Chapter One and forgot about, it gave her dissertation conceptual cohesion. It allowed her to connect her work to a larger scholarly conversation, interpret her results within a broader context, and make meaningful recommendations for practice. When she defended her proposal, her mentor approved and said, “Now you’re not just collecting numbers; you’re telling a theoretical story.”

The theoretical framework chosen for the study should be justified.

In a dissertation, simply describing the theory is not enough. Your readers expect to see:

- A rationale that ties the study’s context, problem, and research questions directly to the chosen theory.

- A comparison that shows awareness of other relevant frameworks and why they were set aside. Some examples that could have been considered. Mentioning other frameworks demonstrates that you have reviewed the landscape and intentionally chosen the framework that you did.

- A conceptual “fit” that explains how the theory’s components will be applied to interpret the findings.

Let’s see how Maya’s mentor used feedback to help her address these points.

Framing the Theory

After reviewing Maya’s continued work, her mentor guided her to address these three key points.

“Maya, you’ve described transformational leadership theory well, but you still need to justify why it’s the right choice for your study. Remember, your committee will expect three things:

-

A clear rationale connecting your problem and questions to the theory.

-

Awareness of other frameworks you considered and why you set them aside.

-

An explanation of how the theory will guide your interpretation of results.”

Maya was prepared as she had done her homework! “Okay, so for the the rationale, I’ll connect transformational leadership directly to my variables. The theory’s components of idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration all map right onto the leadership behaviors I’m measuring as independent variables. And teacher satisfaction and retention intention fit the theory’s prediction that inspired, motivated teams have stronger commitment. That’s the exact mechanism I’m testing.”

Her instructor approved. “Good. That shows you’re not just borrowing the theory’s name, you’re using its structure to design your study. What about the second point?”

Maya replied, “I looked at servant leadership and distributed leadership theories too. Servant leadership focuses heavily on prioritizing followers’ needs, which is valuable, but less aligned with the motivation and commitment aspects I’m measuring. Distributed leadership is about shared decision-making, which matters in schools, but doesn’t focus as directly on the leader–follower dynamic. Transformational leadership just fits my questions better, so I’m keeping that one.”

“Perfect,” her instructor responded. “Make sure you explain that in your dissertation. Now, how will you use the theory when you interpret your results?”

Maya paused to think. “Well, if my data show that higher scores in ‘inspirational motivation’ are linked to higher teacher retention rates, I can interpret that through the theory’s lens. Specifically, how shared vision and enthusiasm contribute to long-term commitment. And if certain components don’t show a relationship, I can discuss possible contextual factors that might limit the theory’s application in these districts. That way, the framework shapes both my design and my conclusions.”

Her instructor smiled approvingly. “Now you’re not just inserting a theory in Chapter One, you’re showing how it threads through your whole dissertation. That’s what your committee will want to see.”

The theoretical framework provides the foundation that connects your study’s problem, purpose, and research questions to a broader body of knowledge, guiding how you design the study, interpret your results, and contribute to theory and practice.

Assumptions

This section outlines the conditions the researcher accepts as true without direct verification, yet are necessary for the study to move forward. Assumptions are not hypotheses to be tested; instead, they are foundational premises that support the research design and methodology. For example, in a survey-based study, the researcher might assume that participants will respond honestly and thoughtfully, and that they will have the ability to recall and report the information requested. In a study using an established instrument from a different context, the researcher assumes the tool has acceptable validity and reliability for the population under investigation, and that it measures the constructs it purports to measure. While any assumptions cannot be proven within the study itself, acknowledging them demonstrates methodological transparency and helps readers understand the context and boundaries of the inquiry (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Limitations and Delimitations

Though limitations and delimitations sound similar, they are not the same thing, and should be addressed with at minimum two separate paragraphs. In short, limitations are constraints to a study that a researcher cannot control while delimitations are constraints that the researcher has deliberately chosen.

Limitations

A limitation is a weakness or constraint the researcher cannot control (Patton, 2015; Mertens, 2020). Typically, limitations are inherent in the nature of the research conducted; while a researcher attempts to remove limitations, they exist in every study.

Common limitations in research are:

- Sample-related limitations

- Small sample size (limits generalizability)

- Non-random sampling (e.g., convenience sample, purposive sample)

- Low response rate in surveys

- Measurement limitations

- Use of self-reported data (risk of bias or inaccurate recall)

- Limited validity or reliability of untested or self-created instruments or surveys

- Single measurement point (cross-sectional rather than longitudinal)

- Design limitations

- Lack of experimental control of variables

- Short study duration that may not capture long-term effects

- Limited number of variables analyzed

- Data collection limitations

- Limited access to relevant populations or settings

- Language or cultural barriers affecting data interpretation

- Ethical or logistical constraints (e.g., inability to randomize participants)

- External limitations

- Context-specific findings (results may not generalize to other settings)

- Rapidly changing conditions (e.g., during a pandemic or technological shift)

- Influence of uncontrollable external factors (e.g., school closures, unexpected interruptions)

There’s no hard-and-fast “correct” number of limitations for a dissertation, but in most doctoral studies, you’ll see somewhere between three and seven clearly stated limitations. Generally, that’s enough to demonstrate that the researcher is aware of constraints, but not so many that the study appears fatally flawed. These numbers are just a general guide, not a hard and fast rule:

1–2 limitations

-

- Too few, and it may look like you haven’t critically evaluated your design.

- Risk: Your committee may think you’re ignoring real methodological weaknesses.

3–5 limitations (common range)

-

- Balanced and realistic; acknowledges constraints while still showing the study’s value.

- Typical for both quantitative and qualitative dissertations.

6–7 limitations

-

- Still reasonable if your study design is complex or involves multiple phases or data sources.

- Often appears in mixed methods studies or multi-site research.

More than 7 limitations

-

- Acceptable only if many are very minor and do not undermine the study’s validity.

- If too many are serious (e.g., major sampling, measurement, or analysis constraints), it can weaken confidence in the findings.

The limitations specific to an study should be written in paragraph form, in sentences such as these examples, as opposed to a bulleted or numbered list.

“This study’s findings are limited by the small, non-random sample, which may affect the generalizability of the results.”

Or

“The use of self-reported surveys introduces the possibility of response bias and inaccurate reporting.”

Delimitations

A delimitation is a boundary that the researcher deliberately sets (e.g., focusing only on one population, using only certain variables), helping narrow the study’s scope (Creswell & Poth, 2018). They define what the study will and won’t cover to ensure that the study is both manageable and relevant. Delimitations clarify for the reader the limits of the study’s scope. Delimitations are set to…

- make the project feasible → Time, resources, and scope are limited, so you can’t study everything.

- focus on the most relevant aspects → By narrowing in on certain populations, variables, or methods, you sharpen your research focus.

- align with the research purpose → Your delimitations ensure that the study stays directly aligned with your purpose, research questions, and hypotheses.

- increase clarity and transparency → You show readers you’ve made intentional choices, rather than leaving gaps or exclusions unexplained.

Examples of delimitations might include choosing to study only one sixth grade class of a school with multiple sixth grade classrooms, limiting the study to one district or region when doing a statistical analysis, or studying only specific variables while not addressing others.

There’s no set number of delimitations a dissertation must have, but most studies include between two and five clearly stated delimitations; enough to clarify the study’s boundaries without overcomplicating its scope.

1 delimitation

-

- Too few, and it may appear you haven’t intentionally defined the study’s scope

- Risk: Readers may not understand the intentional boundaries you’ve set to keep the project manageable.

2–4 delimitations (common range)

-

- Balanced for most dissertation projects.

- Demonstrates intentional choices about participants, setting, timeframe, variables, or theoretical focus.

5+ delimitations

-

- Acceptable if your study involves multiple dimensions (e.g., multi-site, mixed methods, longitudinal).

- Ensure they are clearly grouped so readers can easily see the rationale.

It’s not the number of delimitations that matters most, it’s how clearly you explain that these boundaries are intentional choices you made to make the study feasible, focused, and aligned with your research purpose. Unlike limitations, delimitations are within your control and should reflect strategic design decisions.

Summary

This section briefly wraps up Chapter One in a quantitative study, reviewing the key points covered and preparing the reader for the next chapter, typically the literature review. It reinforces the importance of the study and reminds the reader of the study’s direction. And even though chapter two was written first, this summary introduces the reader to the literature review, as this is the first time that they will read it.

Chapter One in a Qualitative Study

Introduction

The introduction to your study provides an overview of the research topic and introduces the general area of study. Many colleges and universities include a section of Chapter One called “Background Information” as well as the introduction; as Saint Peter’s University does not require that as a separate section, any background information necessary for the reader to understand the topic should be provided in your introduction.

The introduction provides context. This may be historical, cultural, field specific, or anything else that will help the reader understand the setting for your study. It grabs the reader’s attention by outlining the background, setting the stage for the problem, and explaining why you’ve chosen to write about this topic. Note that the introduction is one section that you will want to revisit when your study has been completed. You may have made changes or adjustments in your approach; you may have learned additional context that will be helpful for your reader to understand before delving into your study. When your paper is nearly complete, re-read your introduction to make sure it still rings true, also identifying new information that could be added as a preview to your study.

Statement of the Problem

The introduction has set the stage and provided the reader with enough context to understand the topic you’ve chosen to write about. The next step is to articulate the specific research problem or issue the study addresses. It explains what gap, inconsistency, or unresolved question exists in the current knowledge or practice and why it needs to be investigated qualitatively. The connection between the gap(s) in research found in the literature should not be implied; they must be clearly articulated. This is where the strongest connection is made between your study and past research.

From Curiosity to Problem Statement – A Qualitative Study Journey

Marcus is a doctoral student in the Caulfield School of Education. He works as an academic advisor at a large urban community college. Over the past few semesters, he has noticed something intriguing: some first-generation college students seem to thrive academically despite working long hours and facing personal challenges, while others with similar circumstances struggle to complete their courses. Marcus wonders, what factors shape these very different experiences?

Step 1: Observation and Curiosity

Marcus first considered looking at grade data, but he realized that numbers alone wouldn’t explain the why behind students’ success or struggles. He wanted to understand students’ perspectives in their own words.

Step 2: Reviewing the Literature

His literature search revealed that many studies focused on measurable predictors like financial aid status, course load, and GPA. While some research acknowledged psychosocial factors (such as resilience and sense of belonging), very few studies deeply explored the lived experiences of first-generation community college students balancing work and academics, especially at large urban campuses.

Step 3: Narrowing the Focus

Marcus decided to focus on students in their first year, believing this transitional period is critical to retention. He also realized that how students describe their challenges and supports might provide insights for targeted interventions.

Step 4: Identifying the Approach

Marcus chose a phenomenological approach, aiming to uncover the essence of students’ lived experiences. Instead of predictor and criterion variables, his focus would be on themes emerging from in-depth interviews. He planned to recruit a purposive sample of first-generation, first-year students who were working at least 20 hours a week while enrolled full-time.

Step 5: Writing the Problem Statement

Marcus’s problem statement emerged:

“While prior research has identified certain demographic and academic factors associated with the success of first-generation college students, there is limited understanding of how first-generation, first-year community college students in urban settings experience and navigate the demands of full-time coursework and significant employment responsibilities. At Metro Community College, it is unknown how these students describe the challenges, supports, and strategies that shape their academic journey. Gaining insight into these lived experiences may inform advising practices, student support services, and retention strategies.”

Step 6: Ready for the Next Step

With his problem statement in place, Marcus could now refine his central research question, develop interview protocols, and prepare for data collection.

Significance of the Problem

Once the previous section addresses the question, “What is the problem,” this section answers the question “Why is the problem important?” This section details the potential impact or contribution of the study, showing how the findings could advance knowledge, inform practice, shape policy, or benefit specific groups or fields. Let’s circle back to Marcus. How did he relate the significance of the problem he identified? Notice that not only did Marcus identify how it connects to the specific issue at “Metro Community College,” he also connected it to broader connected issues that merit continued study.

Consider your own problem. It matters to you…it likely matters to the institution and the students in your study. Who else can benefit from the study of your problem?

Significance of the Problem

Marcus set out to articulate the significance of the problem, and why it merits careful study.

The first year of college is a critical period for student retention, particularly for first-generation students attending community colleges in urban settings. While quantitative studies have identified demographic and academic factors associated with persistence, these approaches often overlook the complex, lived realities that influence student success. For first-generation students who work substantial hours while enrolled full-time, understanding how they perceive, experience, and navigate their academic journey can reveal factors not easily captured through numerical data alone.

At Metro Community College, advisors and student support personnel work with limited resources to meet the needs of a diverse student body. Without a clear understanding of the supports, barriers, and coping strategies these students identify as most influential, interventions risk being misaligned with actual student needs. Insights gained from students’ own narratives can inform advising practices, guide the development of targeted retention initiatives, and shape institutional policies that better accommodate the realities of working students.

This study addresses a gap in the literature by focusing on the lived experiences of first-generation, first-year students at an urban community college who also maintain significant employment. By centering students’ voices, the research provides a richer understanding of how academic success is pursued and sustained under challenging circumstances. The findings have the potential to influence not only Metro Community College’s support structures but also broader conversations about equity, access, and persistence in higher education.

Purpose of the Study

This section states the overall purpose (what the study seeks to accomplish). Think of your purpose statement as an “elevator speech.” If someone asked you on an elevator what your research study is about, the purpose statement is a short sentence that you could say in common language to answer that question. It should be explicitly stated and clear; the wording of this should state “The purpose of this study is to…” with a few sentences of explanation or context.

Research Questions

A research question naturally follows the purpose of the study, and spells out what specifically you are aiming to learn about your research problem with your own research exploration.

In qualitative research, these questions are:

- Open-ended (not yes/no).

- Exploratory; that is, they aim to understand meaning, experience, or process, not test a hypothesis.

- Aligned with one of the qualitative methods introduced in the previous chapter (e.g., case study, phenomenology, ethnography).

Here are some examples of well worded, “researchable” questions:

- How do first-generation college students experience academic pressure during their first year?

- What strategies do these students use to cope with stress?

- How does a new intervention program contribute to their confidence in themselves to succeed?

Notice: You are not predicting outcomes or measuring variables, you are seeking rich, descriptive insights. When you construct your research study, it will be designed to directly answer these research questions, which in turn will contribute to meeting the purpose of your study.

Think of your research questions in this way:

- Statement of the problem → here’s the gap we don’t understand.

- Purpose of the Study → a statement of what I intend to accomplish with my research.

- Research questions → here’s exactly what I will explore to meet my purpose and help fill that gap.

Crafting strong research questions is often one of the most challenging steps in the dissertation process. The research question is the bridge between the broad problem you want to address and the specific methods you will use to study it. A well-constructed question guides your design, data collection, and analysis; a poorly constructed one can create confusion, weaken your focus, and undermine the study’s credibility. For this reason, your research questions will very likely go through a number of iterations based on conversations with your Dissertation Seminar I professor, mentor, and committee. You may, in fact, tweak wording throughout the dissertation process, but the essence of the question must remain unchanged.

The most common pitfalls of a research question is that they are too broad/vague or too narrow/focused. Let’s look at examples of how each extreme plays out.

Too broad!

A vague question is broad, unfocused, and difficult to answer with the time, resources, and scope available for a dissertation. It may read more like a topic or curiosity than a targeted inquiry.

Example of “too broad:”

-

How do teachers feel about technology in the classroom?

This research question lacks clarity about which teachers, what kind of technology, what aspects of “feel,” and how those feelings will be explored or measured. Vague questions often lead to unfocused literature reviews, scattered data collection, and results that are hard to interpret.

Better:

- How do middle school English language arts teachers in suburban public schools perceive the impact of interactive whiteboard technology on student engagement during reading instruction?

Why this works:

- It pinpoints the “who” (middle school ELA teachers in suburban public schools)

- It specifies what technology (interactive whiteboards)

- It focuses on a measurable/observable aspect (perceived impact on student engagement in reading)

- The statement is still broad enough to connect to larger literature on educational technology and engagement.

Too Narrow!

An overly narrow question limits the scope so much that the findings have little broader relevance, or the sample becomes too small to generate meaningful results.

Example of “too narrow:”

-

What is the effect of using Duolingo for 15 minutes each day over a two-week period on the Spanish vocabulary test scores of ninth-grade students in Ms. Rodriguez’s third-period English class?

While highly specific, this question may restrict the study to a single context that is not generalizable and may not yield enough data for valid statistical analysis.

Better:

- What is the effect of a daily 15-minute session using a mobile vocabulary application over a four-week period on the vocabulary test scores of ninth-grade students in two suburban high schools?

Why this works:

- It broadens the context and sample (two suburban high schools instead of one class) for more generalizable results

- It identifies a clear intervention (15-minute daily vocabulary app use) and measurable outcome (vocabulary test scores)

- It maintains feasibility while also increasing the potential for meaningful and generalizable statistical findings.

Context is Key! Build a Bridge.

The Research Questions section is not simply a bullet-pointed list of what you plan to ask or study. It’s a bridge between your problem statement, purpose statement, and theoretical/conceptual framework and the methods you will use in the next chapter. This section should provide context, sometimes called the “connective tissue,” that explains how the questions flow logically from the problem, how they align with your framework, and why they are structured as they are.

Without this context, your research questions may appear disconnected or ungrounded. A strong Research Questions section:

- First, it introduces the rationale. It briefly explains why these specific questions are being asked and how they address the problem.

- Second, it links directly to theory/framework. It shows how the questions reflect the theoretical or conceptual lens of the study.

- Finally, it transitions forward, setting up the move into methodology by showing that the questions are both researchable and aligned with the study’s purpose and research methodology.

So if this section is more than just a bulleted list, what does a fully fleshed out version look like? Here’s an example. Notice that there is both connection back and a transition forward, placing the research questions as the bridge between the problem identified and the method of analysis.

Research Questions (example section)

The problem of high rates of teacher attrition in rural school districts has been well documented, with research suggesting that leadership style may influence teachers’ experiences and decisions to remain in or leave the profession (Ingersoll, 2021; Bass, 1985). While prior quantitative studies have measured the statistical relationships between leadership behaviors and retention, far fewer have explored how teachers themselves perceive and interpret their administrators’ leadership styles in relation to their commitment to stay. Guided by transformational leadership theory, this study seeks to capture the lived experiences and perspectives of rural teachers, focusing on how they describe the leadership practices that shape their sense of job satisfaction, professional support, and long-term career decisions. This study will be guided by the folowing research questions:

RQ1: How do rural K–12 teachers describe their administrators’ leadership behaviors in the context of their day-to-day professional experiences?

RQ2: In what ways do teachers perceive these leadership behaviors as influencing their satisfaction with their work and their commitment to remain in the profession?

RQ3: How do teachers explain the connection (if any) between leadership practices and their long-term retention decisions?

These open-ended questions are designed to generate rich, descriptive accounts rather than numerical measurements, making them well-suited for a qualitative research approach. They align with a phenomenological design, in which in-depth interviews provide the primary data for identifying shared themes and meanings. The analysis will focus on coding participants’ narratives to uncover patterns that connect leadership behaviors to teachers’ perceptions of satisfaction and retention, allowing for interpretation through the lens of transformational leadership theory.

As you read this example, ask yourself if you can see the three elements:

- Is the rationale for the research questions introduced? How does it connect back to the problem and the literature review?

- Is it clear how it is linked to the framework chosen for the study?

- Does it transition forward by showing that the questions are both researchable and aligned with the study’s purpose and research methodology?

As you write your research questions sections, contextualizing them in the same manner will make your dissertaiton more cohesive, clearly connecting past research to your own research study.

Definitions of Key Terms

The definition of key terms section provides general conceptual explanations for important terms or concepts in your study, often to clarify meaning for the reader. These are often pulled from literature or theoretical definitions. This section helps orient the reader, especially when terms could be unfamiliar, contested, or have multiple meanings in different contexts. It is important to use established and understood definitions whenever possible to ensure that your research is easily compared to other research studies and generalizable to future research. They should be introduced in an alphabetical list, which will likely continue to grow as your paper develops.

Here are some examples of definitions with citations to show how terminology can be introduced and connected to the field. The corresponding references are provided; in your paper, those references should be included in your references list.

Here are five examples of definitions. Below are deomnstrations of what would need to be added to the dissertations References section.

- Academic Self-Efficacy. Academic self-efficacy refers to a student’s belief in their ability to successfully perform academic tasks or achieve academic goals (Bandura, 1997).

- Attrition. Attrition in higher education refers to the phenomenon of students leaving or dropping out of their academic programs before completing their degree or credential (Tinto, 1993).

- First-Generation College Student. A first-generation college student is typically defined as a student whose parents have not completed a four-year college degree, making them the first in their family to attend and pursue higher education (Pascarella et al., 2004).

- Retention. Retention refers to the ability of an institution to keep students enrolled over time, typically measured by the proportion of students who continue from one year to the next (Seidman, 2005).

- Student engagement. Student engagement is the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, and passion that students show when they are learning or being taught, which extends to their level of motivation to learn and progress in their education (Fredricks et al., 2004).

Corresponding References

These would be added to your paper’s References section.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Pascarella, E. T., Pierson, C. T., Wolniak, G. C., & Terenzini, P. T. (2004). First-generation college students: Additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(3), 249–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2004.11772256

Seidman, A. (2005). College student retention: Formula for student success. ACE/Praeger.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Theoretical Perspective and/or Conceptual Framework

While a quantitative approach is rooted in a theoretical framework, a qualitative study is based on the author’s theoretical perspective. The author may also choose to cast a vision in Chapter One by positing a conceptual framework as well.

Theoretical Perspective

A theoretical perspective is the broad philosophical lens or worldview through which an author of a dissertation views their topic of study. It reflects foundational beliefs about what constitutes knowledge and how it can be known (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Patton, 2015). Common theoretical perspectives include constructivism, positivism, critical theory, and postmodernism (Mertens, 2020). For example, a constructivist perspective assumes that reality is socially constructed and that meaning is developed through individuals’ interactions with their environments and each other (Creswell & Poth, 2018). In qualitative research, a theoretical perspective is identified in existing research or literature and described in Chapter One. At that point, a conceptual framework may be created by the author to explain their perspective and lens to view the topic based on their research, knowledge, and personal experience. For this and the next section on Conceptual Framework, we will take a look at “Elena’s” journey in her qualitative study.

The Search for a Theoretical Perspective

Elena, a doctoral student in the Caulfield School of Education, had been teaching high school English for nearly fifteen years before starting her dissertation. For her qualitative study, she wanted to explore how recently immigrated high school students adapt socially and academically during their first year in a U.S. school. She envisioned sitting down with students, listening to their stories, and capturing the richness of their experiences in their own words.

In Dissertation Seminar I, her professor asked her to consider, “What theoretical perspective will guide your study?”

Elena wasn’t sure what it was or how it fit. “I thought I needed a conceptual framework?”

Her professor expalined, “They’re related, but not identical. Your theoretical perspective is your philosophical lens. It’s the worldview through which you see your topic. It shapes what you believe counts as knowledge and how you think it can be discovered. Once you’ve established that, you can build your conceptual framework to explain your specific lens for this study.”

Equipped with this knowledge, Elena began reading about different perspectives. She quickly ruled out positivism because it relied too heavily on objective measurement for the kind of meaning-making she wanted to capture. Critical theory was appealing, but its strong emphasis on uncovering systems of oppression didn’t fully match her primary aim, which was understanding how students themselves construct meaning from their experiences.

Then she encountered constructivism in the works of Creswell and Poth (2018) and Patton (2015). The idea that “reality is socially constructed” resonated deeply with her. She believed each student’s account would be shaped by their interactions, backgrounds, and cultural identities, and that there was no single “truth” to uncover, but multiple realities to account for.

With this perspective chosen, Elena reframed her study. She explained in Chapter One that she would approach interviews and analysis through a constructivist lens, assuming that the meaning of “adaptation” would differ for each participant, and that her role was to co-construct understanding through dialogue.

But what about her conceptual framework? To be continued!

Conceptual Framework

In a qualitative study, the conceptual framework serves as the researcher’s own map of how they understand the problem, what they believe are the key constructs involved, and how those constructs relate to each other. It is typically built by the researcher, informed by prior literature, personal insights, observations, the theoretical perspective, and contextual understanding (Miles et al., 2014). While the theoretical perspective provides the broad philosophical lens (such as constructivism or critical theory) through which the researcher approaches the world, the conceptual framework lays out the specific “what:” the particular concepts, assumptions, and proposed relationships that shape the design of the study.

For example, a researcher studying first-generation college students might draw from existing studies on self-efficacy, institutional support, and student persistence to create a conceptual framework showing how these constructs interact. This framework will guide the development of research questions, selection of participants, data collection methods, and interpretation of findings. Importantly, the conceptual framework is unique to the individual study: it reflects the researcher’s synthesis of the relevant ideas, rather than simply applying an established external theory.

As Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (2014) explain, a strong conceptual framework makes your research more intentional and focused, clarifying your thinking and making your study design coherent. It also provides a valuable guide for your readers, helping them understand the logical connections behind your research choices.

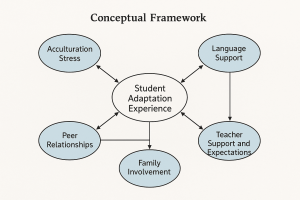

Let’s revisit Elena, and see how she applied a conceptual framework to her study.

Continuing the Story: Elena Builds Her Conceptual Framework

Once Elena had committed to a constructivist theoretical perspective, she realized she now needed to articulate the specific ideas that would guide her study. This would be her conceptual framework.

Her dissertation professor explained it this way: “Your theoretical perspective is like the lens in your camera. It shapes how you look at the world. Your conceptual framework is the photograph you’re trying to capture. It shows what’s in focus for this particular study.”

Elena began by revisiting the literature she had reviewed earlier. She noted recurring themes in research on immigrant high school students, and had divided her literature review into the relevant sections:

- Acculturation stress

- Peer relationships and social belonging

- Language acquisition challenges and supports

- Teacher expectations and instructional practices

- Family involvement and cultural identity

She also thought about her own classroom experiences. She remembered students who thrived because they found a small group of friends who shared their language, and others who gained confidence when teachers paired them with supportive peers. She recalled how school orientation programs varied in effectiveness, and how students’ sense of belonging often determined whether they participated in class discussions.

From there, Elena began sketching a diagram on a large sheet of paper. At the center, she placed Student Adaptation Experience. Around it, she drew five interconnected circles, each representing one of the key constructs she believed shaped that experience:

- Acculturation Stress

- Language Support

- Peer Relationships

- Teacher Support and Expectations

- Family Involvement

She connected the circles with arrows, some pointing toward the central “Student Adaptation Experience,” others linking constructs to each other. For example, she drew an arrow from “Peer Relationships” to “Language Support,” reflecting her observation that friendships often helped language development. She also connected “Family Involvement” to “Acculturation Stress,” noting that strong family support sometimes reduced the emotional burden of transition.

Conceptual framework for student adaptation experience in immigrant high school students. Adapted from an original diagram generated by ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025).

This conceptual framework became more than a diagram, it was Elena’s personalized map of the problem. It reflected:

- Her constructivist worldview (recognizing that each student’s adaptation is uniquely shaped by multiple, interacting factors)

- Insights from prior research (drawing on existing studies of immigrant student adaptation)

- Her professional experience (patterns she had observed in her own teaching)

- Her assumptions (such as believing that peer support can mediate the challenges of language learning)

In Chapter One, Elena described each construct, explained the relationships she proposed, and clarified that this framework would guide her research questions, participant selection, interview protocol, and analysis.

When complete, her mentor was pleased that she could see the coherence: her constructivist perspective shaped how she would approach the study, and her conceptual framework clearly laid out the specific elements she would explore. As her dissertation professor told her in the assignment feedback, “You’ve shown both the lens and the map. Now everyone can see exactly how you plan to navigate your research.”

Whether you use both a theoretical perspective and a conceptual framework, or just one or the other, is a healthy conversation to have with your Dissertation Seminar I professor and to elaborate upon with your mentor. As you can see, these elements add clarity to your research assumptions (to be addressed next) and methodology.

Assumptions

This section outlines the conditions the researcher accepts as true without direct verification, yet are necessary for the study to move forward. Assumptions are foundational premises that support the research design and methodology. For example, in a survey-based study, the researcher might assume that participants will respond honestly and thoughtfully, and that they will have the ability to recall and report the information requested. In a study using an established instrument from a different context, the researcher assumes the tool has acceptable validity and reliability for the population under investigation, and that it measures the constructs it purports to measure. In qualitative interviews, assumptions might include the belief that participants will feel comfortable sharing their experiences openly or that the researcher can accurately interpret the meaning of their responses. While any assumptions cannot be proven within the study itself, acknowledging them demonstrates methodological transparency and helps readers understand the context and boundaries of the inquiry (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Limitations and Delimitations

Though limitations and delimitations sound similar, they are not the same thing, and should be addressed with two separate paragraphs. In short, limitations are constraints to a study that a researcher cannot control while delimitations are constraints that the researcher has deliberately chosen.

Limitations

A limitation is a weakness or constraint the researcher cannot control (Patton, 2015; Mertens, 2020). Typically, limitations are inherent in the nature of the research conducted; while a researcher attempts to remove limitations, they exist in every study.

Common limitations in quantitative research are:

Sample and Context Limitations

- Small or narrowly defined participant group may limit the transferability of findings to other settings.

- Purposeful or convenience sampling may exclude alternative perspectives.

- Limited diversity among participants (e.g., all from one institution or region) may reduce contextual variation.

Researcher and Data Interpretation Limitations

- The researcher’s own background, assumptions, or positionality may influence data collection and interpretation.

- Subjectivity in coding or interpreting qualitative data can affect consistency.

- Researcher–participant relationships may shape participants’ responses (e.g., social desirability or power dynamics).

Data Collection and Scope Limitations

- Data collected from a single site, setting, or case may not capture wider variation.

- Time constraints may prevent prolonged engagement or repeated observations.

- Incomplete or uneven data (e.g., missing interviews, low participation in focus groups) may narrow insights.

- Language or cultural barriers can complicate meaning-making and interpretation.

Analytic and Methodological Limitations

- Use of a single data collection method (e.g., only interviews) may limit depth or triangulation.

- Emergent themes may not fully align with initial research questions or theoretical framework.

External and Contextual Limitations

- Findings may be context-specific and not easily transferable to other populations or settings.

- Changing social, institutional, or policy contexts (e.g., post-pandemic shifts, leadership changes) may influence participants’ perspectives.

- Ethical or logistical constraints (e.g., inability to record sensitive interviews) can limit data richness.

There’s no hard-and-fast “correct” number of limitations for a dissertation, but in most doctoral studies, you’ll see somewhere between three and seven clearly stated limitations, generally enough to demonstrate that the researcher is aware of constraints, but not so many that the study appears fatally flawed. These numbers are just a general guide, not a hard and fast rule:

1–2 limitations

-

- Too few, and it may look like you haven’t critically evaluated your design.

- Risk: Your committee may think you’re ignoring real methodological weaknesses.

3–5 limitations (common range)

-

- Balanced and realistic; acknowledges constraints while still showing the study’s value.

- Typical for both quantitative and qualitative dissertations.

6–7 limitations

-

- Still reasonable if your study design is complex or involves multiple phases or data sources.

- Often appears in mixed methods studies or multi-site research.

More than 7 limitations

-

- Acceptable only if many are very minor and do not undermine the study’s validity.

- If too many are serious (e.g., major sampling, measurement, or analysis constraints), it can weaken confidence in the findings.

The limitations specific to an study should be written in paragraph form, in sentences such as these examples, as opposed to a bulleted or numbered list.

“This study’s findings are limited by the small, non-random sample, which may affect the generalizability of the results.”

Or

“The use of self-reported surveys introduces the possibility of response bias and inaccurate reporting.

Delimitations

A delimitation is a boundary that the researcher deliberately sets (e.g., focusing only on one population, using only certain variables), helping narrow the study’s scope (Creswell & Poth, 2018). They define what the study will and won’t cover to ensure that the study is both manageable and relevant. Delimitations clarify for the reader the limits of the study’s scope. Delimitations are set to…

- make the project feasible → Time, resources, and scope are limited, so you can’t study everything.

- focus on the most relevant aspects → By narrowing in on certain populations, variables, or methods, you sharpen your research focus.

- align with the research purpose → Your delimitations ensure that the study stays directly aligned with your purpose, research questions, and hypotheses.

- increase clarity and transparency → You show readers you’ve made intentional choices, rather than leaving gaps or exclusions unexplained.

Examples of delimitations might include choosing to study only one sixth grade class of a school with multiple sixth grade classrooms, limiting the study to a focus group of administrators, or studying only specific variables while not addressing others.

There’s no set number of delimitations a dissertation must have, but most studies include between two and five clearly stated delimitations; enough to clarify the study’s boundaries without overcomplicating its scope.

1 delimitation

-

- Too few, and it may appear you haven’t intentionally defined the study’s scope

- Risk: Readers may not understand the intentional boundaries you’ve set to keep the project manageable.

2–4 delimitations (common range)

-

- Balanced for most dissertation projects.

- Demonstrates intentional choices about participants, setting, timeframe, variables, or theoretical focus.

5+ delimitations

-

- Acceptable if your study involves multiple dimensions (e.g., multi-site, mixed methods, longitudinal).

- Ensure they are clearly grouped so readers can easily see the rationale.

It’s not the number of delimitations that matters most, it’s how clearly you explain that these boundaries are intentional choices you made to make the study feasible, focused, and aligned with your research purpose. Unlike limitations, delimitations are within your control and should reflect strategic design decisions.

Summary